As Canada races to cut its greenhouse gas emissions to net-zero over the next two decades, many people have asked a simple question: How exactly are we going to do this now?

On March 29, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government took a shot at answering that question by laying out a plan for what the country must do by 2030, targeting a 40 per cent reduction from 2005 level-emissions.

That’s the low-end of its commitment to achieve at least a 40- to 45-per-cent reduction in emissions in that time frame. The plan was simultaneously praised for its granularity of detail, as sets out objectives on a sector-by-sector basis, and year by year assigns targets and proposed methods to achieve reductions. But the plan also was lambasted for blind spots and unfairness in some places. For example, there are few details about how the oil industry will be expected to meet its targets.

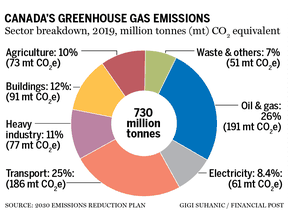

Here’s what the plan means for the country’s largest sectors:

Oil and gas

Since 2005, many sectors, such as heavy industry and electricity, have found ways to cut emissions; but not oil and gas, where production and emissions have risen by 20 per cent. Under the proposed pathway laid out in the plan, that era is over: It calls for a 31 per cent reduction from 2005 emissions levels over the next eight years.

Some people may wonder whether the oil and gas sector is ready for what will surely be a challenge, considering emissions from Alberta’s oilsands have risen 137 per cent since 2005.

“There’s no question it is ambitious,” said Tristan Goodman, president of the Explorers and Producers Association of Canada, a lobby group representing 140 of Canada’s oil and gas entrepreneurs. “The problem we always have in the oil and gas business is we continue, actually, on a per unit basis to reduce emissions — I mean we’re spending billions of dollars every year,” he continued. “The problem is the product is still in demand.”

In other words, the emissions released per barrel of oil have decreased, but the number of barrels produced has increased markedly since 2005 as Alberta’s oilsands grew.

Goodman said the achievability of the plan will depend on how pragmatic the federal government is. He said many companies are waiting for the budget on April 7, which is expected to include a tax credit for expenditures on carbon capture technology.

Interestingly, the plan foresees oil production growing by between 21.7 and 33.9 per cent over the next eight years. The bet is that new technology will help reduce overall emissions.

The problem is the product is still in demand

Tristan Goodman

Many environmentalists criticized the plan’s treatment of oil and gas sector emissions, which only consider emissions released during production, and not emissions released from burning them as fuels.

“It should reduce emissions more commensurate with its fair share in the 40 to 45 per cent realm,” said Simon Dyer, deputy executive director of Pembina Institute, a clean energy think-tank. “Pembina is certainly of the view that there’s plenty of room for the oil and gas sector to reduce emissions.”

Julia Levin, a senior climate and energy program manager at Environmental Defence, an advocacy group, also noted that the oil and gas sector’s 31-per-cent reduction from 2005 levels is less than the country’s overall 40-per-cent reduction.

“From civil society’s perspective, hurtling towards catastrophic climate change, this number is way too low,” said Levin. “There’s a pattern where we ask Canada’s oil and gas sector to do less than any other sector, and then we pay them.”

Levin’s organization has been a staunch critic of the idea that taxpayers should help shoulder the costs for carbon capture technology in the oil and gas production, including questioning the efficacy of such technology.

That debate is likely to roar to life when the federal government unveils its budget in the weeks ahead, and finally announces what it has in mind, if anything at all, in terms of a tax credit for carbon capture technology.

Transportation

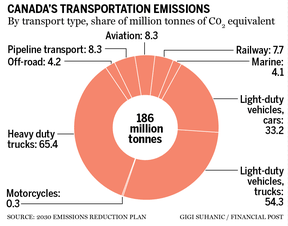

The second-largest source of emissions in Canada comes from transportation, which emitted 186 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent in 2019, or 25 per cent of the country’s total.

During his election campaign last summer, Trudeau signaled that his government wants all new vehicles sold in Canada to be zero-emission by 2030. His plan revealed that those targets will be mandatory.

The plan also sets a new target: 20 per cent of all new vehicles sales will be zero-emission by 2026. That’s only four years away. EVs currently represent only about six per cent of sales.

Brian Kingston, president of the Canadian Vehicles Manufacturers Association, a lobby group for automakers, took issue with the mandates and said the government needs to invest more money — in electric vehicle charging infrastructure and in the electrical grid to support that transition and in incentives for battery electric vehicles.

“If you look at the leading jurisdictions in the world, they’re just far more ambitious in terms of laying out a charging infrastructure,” said Kingston, referring to Norway and Iceland.

The decision is so obvious that you should buy an EV

Brian Kingston

Some numbers: The country currently has about 15,000 chargers for electric vehicles, Kingston said. It needs one charger for every seven to 10 electric vehicles, he added.

The federal government has said it intends to help provide $400 million in support for the development of 50,000 additional chargers, but by Kingston’s metrics above, approximately double that amount is needed. Of course, industry may build some charging infrastructure, as has been the case up until now.

Kingston argued that we also need more electrical transmission capacity, and that without more investment from government, electric vehicles will be more expensive and less desirable.

“Just look at the jurisdictions that are doing this right, Norway and Iceland,” Kingston said. “They focus on building out infrastructure, providing an overwhelming suite of incentives … tax reductions, access to free municipal parking, access to high occupancy lanes, you name it they do it, so as a consumer you got to a lot and the decision is so obvious that you should buy an EV.”

Electricity

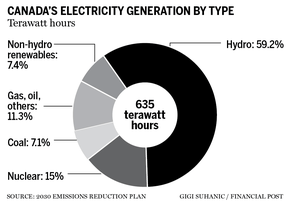

The electrical grid, responsible for 8.4 per cent of total emissions, will face the steepest mandate to decarbonize, with the federal government’s plan envisioning a 77-per-cent reduction in emissions from today’s 61 million tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent, to 14 million tonnes in 2030.

Much of that will come from the phasing out of coal-fired power plants in Alberta, Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia.

Richard Carlson, director of energy policy at Pollution Probe, a non-governmental organization in Toronto focused on the energy transition, said electrical grids are traditionally provincially regulated, so it is difficult for the federal government to direct policy.

Still, he said there will be additional investments needed to increase electrical capacity in order to meet current targets.

Heavy Industry

Heavy industry, which includes the country’s steel, cement, aluminum, mining, fertilizers and other industrial sectors, receives perhaps the lightest treatment in the document.

Although it accounts for 11 per cent of the country’s emissions, these sectors have decreased emissions by a combined 10 per cent since 2005. Still, the plan calls for a 32.4-per-cent reduction from current levels, which would drop heavy industry’s carbon-dioxide equivalent to 52 million tonnes by 2030.

Jean Simard, president of the Aluminum Association of Canada, said that historically many industries, including aluminum, have been huge emitters, but in recent years have worked hard to develop cleaner, more efficient processes.

For example, Simard said that aluminum makers have invested $13 billion in smelters in the past two decades to modernize the production process.

We started doing our homework many many years ago

Jean Simard

It helps that the country’s smelters, which are highly energy intensive sites, are all located in Quebec and British Columbia, where they connect to a grid largely powered by hydroelectricity.

Still, Rio Tinto Ltd., Alcoa Corp., the Quebec and federal governments, and Apple Inc. have invested to develop a carbon-free aluminum process that is expected to be commercialized in the next few years.

Meanwhile, the federal government has used its $8 billion Strategic Innovation Fund to help industry decarbonize, including spending hundreds of millions to help the country’s steel plants convert to electrical arc furnaces, to move away from metallurgical coal and reduce emissions.

“We started doing our homework many many years ago,” said Simard, “whereas other sectors still have a long way to go, they’re still in a long haul.”

What does it all mean?

At more than 230 pages plus an index, the plan is voluminous and chock full of details about the country’s emissions profile and economy. There’s lots more about how to decarbonize buildings, agriculture, and waste, which in 2019, respectively, accounted for 12 per cent, 10 per cent, and 7 per cent of Canada’s emissions.

“Climate change is the biggest challenge facing humanity today,” Steven Guilbeault, the environment minister, said in a video released alongside the plan. “Canadians have what it takes to meet the moment.”

But whether Canada can realistically achieve a 40-per-cent reduction in emissions remains questionable. Emissions dropped 8.8 per cent from 2019 until 2020 — when the pandemic started — and remained flat in 2021, according to the document.

Climate change is the biggest challenge facing humanity today

Steven Guilbeault

Emissions are projected to rise in 2022, minimally, by one megatonne of carbon dioxode equivalent. The following year, 2023, will create the first test when the government projects a two per cent drop in emissions and continue to accelerate modestly over the rest of the decade.

“This is the first rigorous plan,” said Dyer, of the Pembina Institute. “The modelling seems pretty rigorous.”

The plan talks about carbon pricing contracts that would lock in prices so that even if the government party changes during an election, such prices could not change.

“Given the level of leadership from the federal government on the climate file,” he said, “I do think it’s a bit unfortunate that we haven’t seen climate plans from the provincial governments.”

“It’s a shared responsibility,” he added.

Goldy Hyder, head of the Business Council of Canada, praised the plan, calling the targets “ambitious” and noting that “Canadian businesses will need to invest many billions of dollars in new, emission-reducing technologies.”

Hyder noted that this will require a “predictable policy environment” to guide investment in lower-carbon projects, technologies and infrastructure.

“This plan goes further than anything seen to date in spelling out how Canadians can get there,” Hyder said in a statement. “But there are still a lot of unanswered questions ahead, and much heavy lifting.”

• Email: [email protected] | Twitter: GabeFriedz

You can read more of the news on source