Around the world, from China to California, the number of people buying electric cars is doubling every year.

Car manufacturers are ramping up production and announcing new zero-emission models at a rapid pace.

But if a Torontonian wants to join the electric-driving revolution, they’ll have to wait.

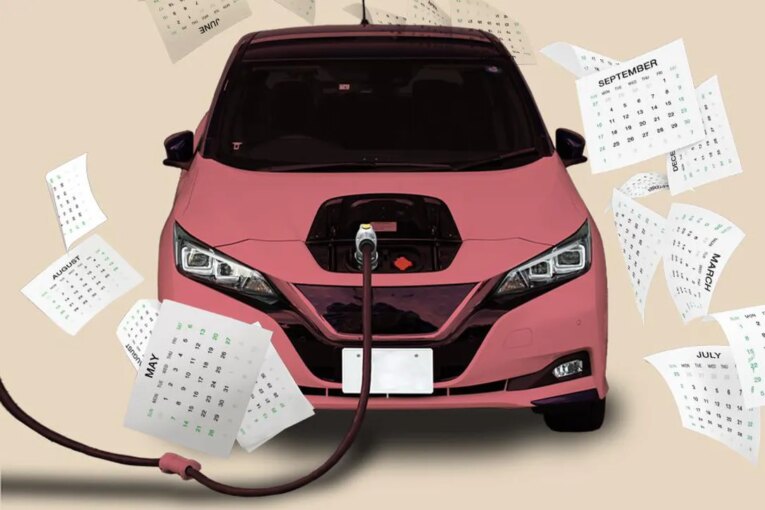

And wait and wait.

Wait-lists for a new zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) in Toronto are almost 11 months long on average, according to a Star survey of dealerships from every major brand and company in the city.

That’s far longer than prospective ZEV buyers have to wait elsewhere. In Quebec, no dealership wait-list was longer than six months, according to a nationwide survey done for Transport Canada last year.

While the international chip shortage has snarled supply chains for all vehicles, exploding demand for ZEVs has made them even harder to get your hands on. Couple this with laws in British Columbia and Quebec that require car companies to sell a certain proportion of electric vehicles and the resulting situation is that when ZEVs roll off the line, they’re sent to those provinces first.

All this leaves Toronto drivers in the lurch. They will have to keep their gas guzzlers on the road for months — or years — longer while waiting for their new ZEV to arrive.