Think oil prices are sky high today?

How about US$120 a barrel — or even $185?

As global oil prices soared this week — U.S. benchmark crude jumped by $8 on Friday to close above $115 a barrel — a report by JP Morgan warned the market could move higher yet.

“In the immediate term, so large is the supply shock that we believe (the) price needs to increase to $120 per barrel and stay there for months to incentivize demand destruction,” analyst Natasha Kaneva wrote in a research report on Thursday.

“Were disruption to Russian volumes to last throughout the year, Brent oil price could exit the year at $185.”

Surging prices and demand destruction — those words are now confronting the global oil industry in a way that hasn’t been seen in years.

It sparks an uncomfortable question: At what point are prices simply too high, even for petroleum producers or a resource-rich province like Alberta, causing inflation to heat up, the global economy to cool down and consumers to get squeezed?

“High oil prices really aren’t great for anybody. In energy-producing regions, there’s a lot of interest and excitement about prices when oil pushes past $80,” said Kevin Birn, vice-president at energy consultancy IHS Markit.

“But the longer-term consequences are also not good, even for the producers … People will try to reduce their use of energy because it’s eating into their disposable income too much and so you get demand destruction.”

And what is the optimum level for Canadian oil producers watching jittery markets race ahead with oil now above $100 a barrel?

“Anything above $65, the sector is doing well and making money and able to return capital to shareholders. In that $75 to $80 range, everything seems to work well,” Crescent Point Energy CEO Craig Bryksa said in an interview Friday.

“As you blow past $100, that starts to heat things up, create a little bit of extra inflation and, at the same time, it can start to push down some of the demand. So it’s a balance.”

You can forgive the industry for feeling a sense of price whiplash coming out of the COVID-19 pandemic and recession.

In the spring of 2020, West Texas Intermediate crude prices crashed below $20 a barrel, falling into negative territory briefly that April.

Prices were on the mend in 2021 and have shot up by more than 50 per cent this year. The trigger to the recent volatility is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which has sent shock waves through global energy markets and propelled prices upward.

Western Canadian Select heavy oil closed at US$102.57 a barrel on Friday, reaching its highest point since August 2008.

Profits and cash flow levels are revving up across the oil industry. The province expects to balance its books this year for the first time since 2014.

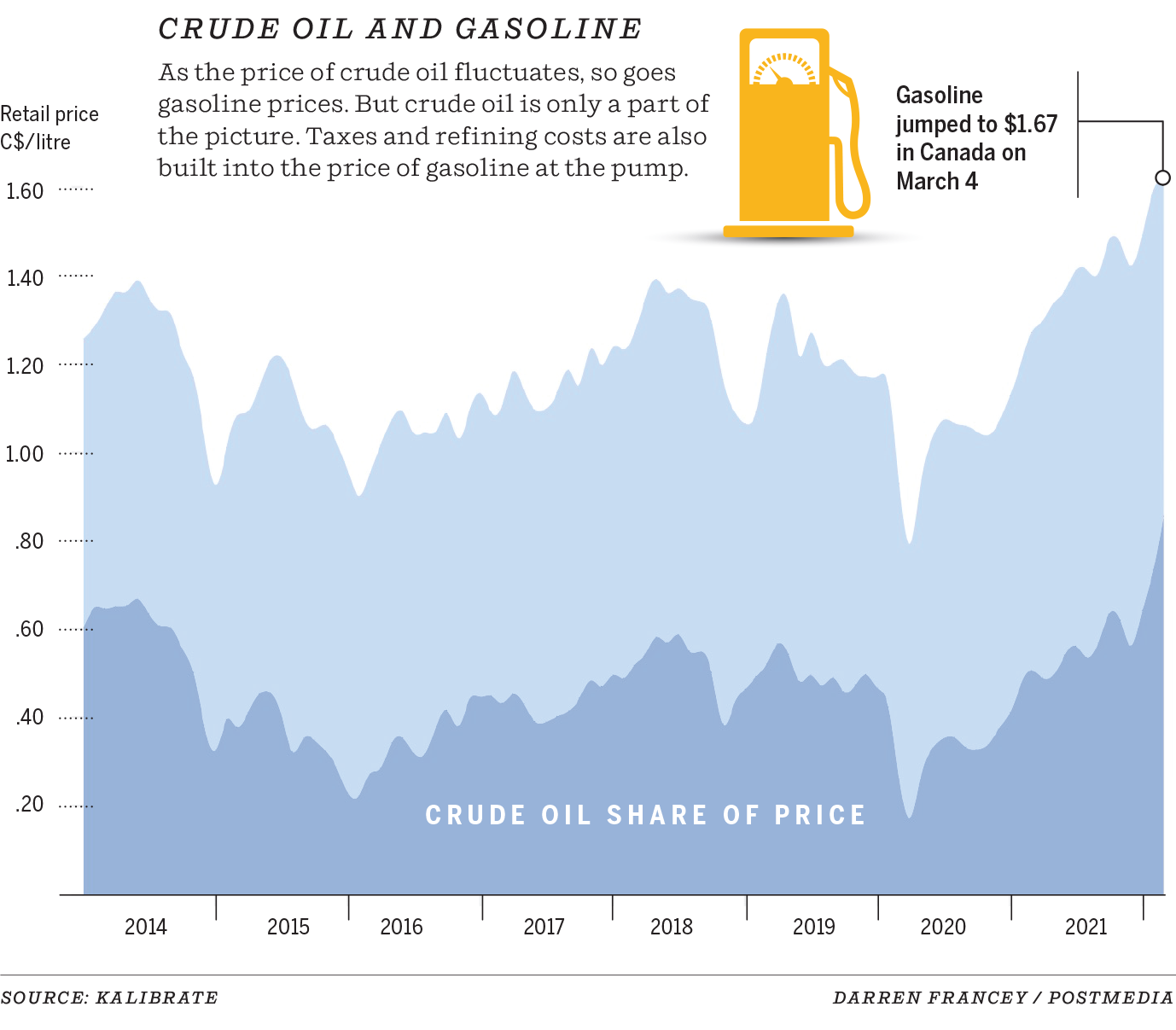

Higher commodity prices have also pushed Canadian pump prices to record levels.

Premier Jason Kenney announced Friday the province is examining ways to help Albertans cope with rising energy costs and the “sticker shock when we go to fill up our gas tank or open our utility bill.” He suggested the province may trim its 13-cent-a-litre gasoline tax.

Even companies in the oilpatch are facing inflationary pressures, from higher steel and labour costs to rising expenses for natural gas used by thermal oilsands producers.

“High energy prices are tough for everybody … any time you have these spikes, it puts a lot of stress on the system,” said Tim McKay, president of Canadian Natural Resources, the country’s largest petroleum producer.

“I personally believe prices will stabilize and be lower. But in the short term here, you see this volatility.”

Much of the volatility in recent days has been driven by geopolitical factors.

While Canada has moved to ban Russian oil and petroleum imports, energy products have largely been exempted from wide-ranging sanctions adopted by western countries.

South of the border, speculation is growing that sanctions on Russian oil are coming soon from the Biden administration.

It’s already clear “Russian oil is being ostracized” as two-thirds of the country’s crude is struggling to find a buyer this week, according to JP Morgan.

“Buyers are standing off from snapping up discounted cargoes of Russia’s Urals crude because they are worried what are the terms and what are the risks of sanctions. We call it self-sanctioning,” said Ann-Louise Hittle, vice-president of oil markets at Wood Mackenzie.

“The longer the crisis goes on, then clearly the ratcheting up of sanctions is going to occur … and this is what the market is anticipating.”

Heading into the crisis, oil prices were already moving higher, starting the year at $76 a barrel.

Before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, global energy demand was expected to recover this year to pre-pandemic levels of around 100 million barrels per day, while supplies were tight.

“We were facing some substantially higher prices than we’ve seen in the last five years just because of (global) underinvestment — and it takes high prices to incent new investment,” said Tim McMillan, head of the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers.

Canadian producers are cautiously increasing spending to increase output, while returning more money to shareholders and paying down their debt.

At Crescent Point, Bryksa said the company will stick with its approved capital program of about $860 million this year, noting it built in an “inflationary bucket” of about 10 per cent to account for rising costs.

For consumers, higher pump prices are already triggering a limited response as drivers feel the pinch, said industry expert Vijay Muralidharan, director of consulting at Kalibrate.

Average Canadian gasoline prices climbed to a record $1.61 per litre earlier this week. Every $1-a-barrel increase in benchmark oil prices causes gasoline rates to climb by 0.65 cents a litre.

If oil hovers around $120 a barrel, Muralidharan estimates average gas prices will fluctuate between $1.65 and $1.75 a litre.

“Expect higher prices for the next two months, at least,” he said.

Add it all up and sizzling energy prices are starting to scorch consumers, while demand destruction and inflation become growing concerns for a province used to commodity price gyrations.

“I don’t think anybody in the sector wants to see things go up too high, too quickly,” said analyst Jeremy McCrea with Raymond James.

“Long term, these price spikes are harmful.”

Chris Varcoe is a Calgary Herald columnist.

You can read more of the news on source