A new federal limit on greenhouse gas emissions is coming for the Canadian oil and gas industry.

Does it mean the end of growth for a key sector of the economy?

Will it cause investment, jobs and production to shift outside of the country?

Or will it activate massive spending in new emissions-reduction projects?

So many questions. So little clarity. So much is at stake.

“We are not particularly fussed by a cap on emissions, subject to a couple of provisos,” Cenovus Energy CEO Alex Pourbaix said in an interview Wednesday.

“Those caps must correspond to the industry’s ability to actually, physically reduce its GHG emissions . . . These are things that cannot be done overnight.”

Pourbaix, who is chair of the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP), also believes a price on carbon needs to be applied globally.

It’s something Prime Minister Justin Trudeau pushed for at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow this week — and something that isn’t in place in the United States.

Aside from the federal government’s plan to cap oil and gas emissions, Ottawa has already established a national price on carbon, which is set to rise to $170 by the end of this decade.

While the U.S. and more than 100 other countries have signed on to reducing methane emissions by 30 per cent by the end of 2030, Canada has gone further, announcing a planned cut of 75 per cent.

A price on carbon needs to be applied globally “so that early movers like Canada, in terms of decarbonizing their economy, are not handicapped by other countries that have no interest in pricing carbon or putting any restrictions on their industry,” said Pourbaix.

The international climate conference in Scotland will help determine just how ambitious countries are prepared to be in the coming years.

At COP26, Trudeau announced his government will become the first major oil and gas-producing county to adopt such an emissions cap on the industry.

Back at home, Ottawa remains in discussion with the sector on a proposed federal tax credit for carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS) projects, which would sequester CO2 emissions underground.

The technology could make a major difference for oilsands operators and other industrial sectors as the country strives to reach its net-zero target by 2050.

On Wednesday, ConocoPhillips Canada joined an alliance of five other major oilsands producers, including Cenovus and Suncor Energy, that have agreed to jointly pursue net-zero emissions within three decades.

“What it really does is just show the interest right across our entire industry in reducing emissions,” said Al Reid, director of the alliance.

The group has said its longer-term plans could cost up to $75 billion over three decades; it is seeking federal assistance to help foot the bill.

Alberta has called for at least $30 billion in federal incentives over the span of a decade.

“People forget we’re actually pretty aligned with the federal government on this. They have a net-zero target in 2050 and that’s the same target we have come out with,” said Pourbaix.

These two sides are singing from the same song sheet, for now.

But Premier Jason Kenney vowed earlier this week his government will fight any anti-oil push to “leave it in the ground.”

As for future oil and gas production increases in Canada, that will depend on several factors, including commodity prices, investor pressure and the ability of companies to move product to markets.

“It obviously depends on where the cap is set,” said Pourbaix.

“I expect on a go-forward basis, you will continue to see growth, but it’s going to be a lot more measured.”

The federal government has referred many of these tough questions about the emissions cap to its net-zero advisory board. The group will face an enormous challenge to help the government establish five-year milestones for the industry.

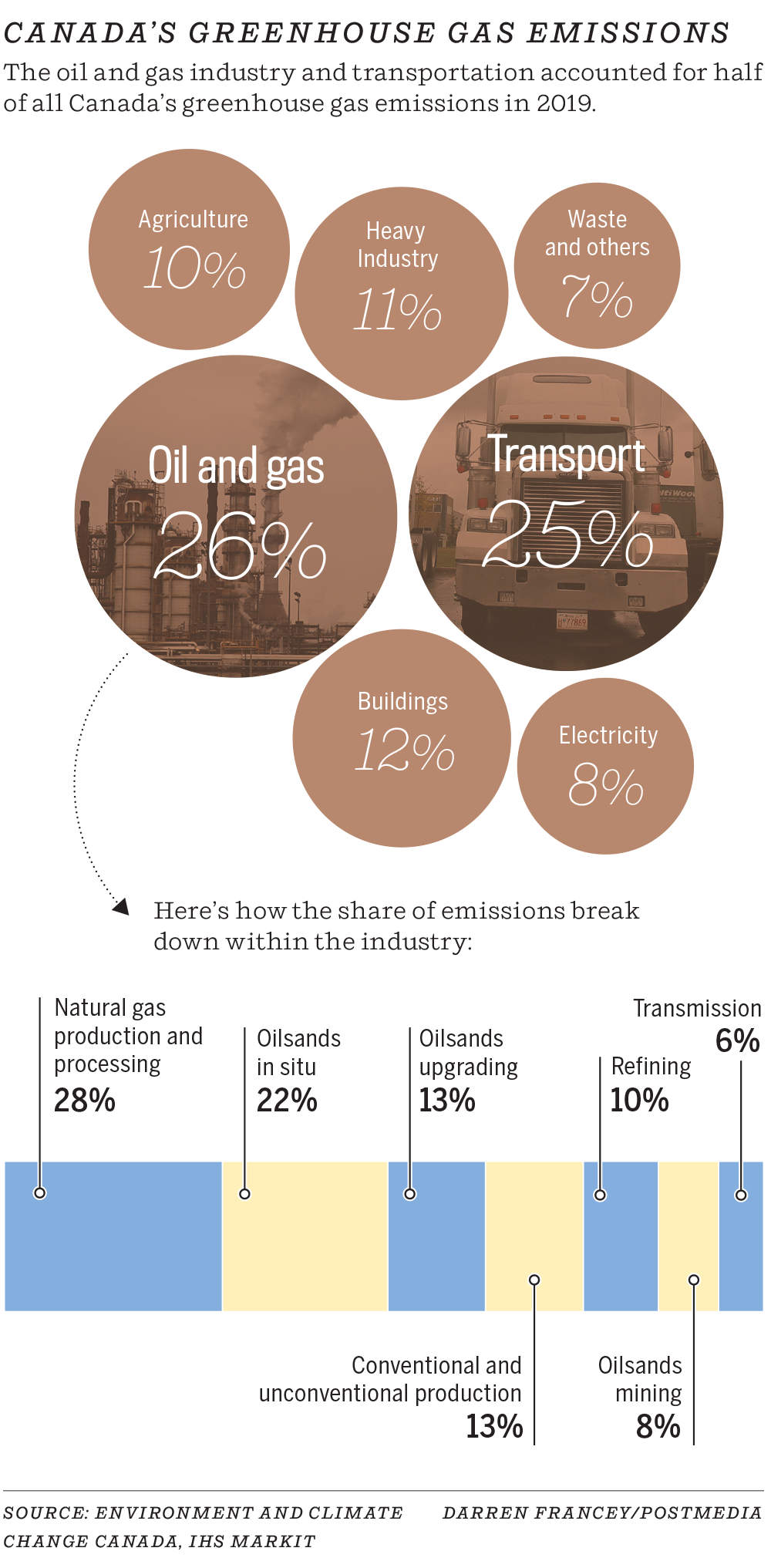

According to federal officials, the cap will apply to emissions from conventional oil and natural gas production, as well as the oilsands.

So far, there has been little communication with the province or industry players about details of the federal limit.

The head of the Explorers and Producers Association of Canada (EPAC) said companies are committed to lowering their emissions, but the group’s members — small and intermediate-sized producers — are frustrated by a lack of consultation from Ottawa.

“There’s been no engagement whatsoever from anyone in the federal government on the cap. We have no idea what it is,” said EPAC president Tristan Goodman.

If these federal measures serve to crimp production, it could push investment and jobs into other oil-producing countries that don’t have the same rules in place.

“Leadership is a good thing until you’re out leading and no one is following — and then you are just all by yourself,” said energy consultant Greg Stringham.

The provincial government already has a 100-megatonne emissions cap on the oilsands, which was adopted by the former Notley government, although the implementing regulations are not in place.

Total emissions from the oilsands sector (as defined by the provincial cap) reached 64 megatonnes in 2019, although the federal government views it as being closer to 83 megatonnes under its criteria, said analyst Kevin Birn of energy consultancy IHS Markit.

IHS has projected oilsands emissions peaking within the decade (even before the oilsands alliance was formed and adopted tougher targets) while total Canadian oil production is projected to climb until the early 2030s.

However, much will depend on the new federal limit.

“A cap on oil and gas emissions, if it is too stringent and too soon, will reduce and throttle production output,” said Birn.

“And when it does that, those production barrels aren’t necessarily going to disappear from the world. They just won’t be produced by Canada.”

Chris Varcoe is a Calgary Herald columnist.

You can read more of the news on source