A spill from the Keystone pipeline. A deeper discount on the price of Western Canadian Select heavy crude.

Canadian petroleum producers could be forgiven for feeling a bit of déjà vu these days.

The spill last week from TC Energy’s Keystone pipeline into a creek in northeastern Kansas — the largest in the pipeline’s history — harkens back to a smaller one in South Dakota in November 2017.

That incident sparked a sudden widening in the price differential between U.S. benchmark West Texas Intermediate (WTI) crude and Western Canadian Select (WCS) oil. It preceded a much bigger challenge for the sector the following year: a massive blowout in the heavy oil price discount, which eventually led to production quotas.

And it underscored a chronic headache for the sector: a razor-thin balance between production and pipeline capacity out of Western Canada, which can quickly be sidetracked by an unexpected problem.

Flash forward to December 2022.

The landscape has shifted with increased storage capacity, the completion of Enbridge’s Line 3 replacement project and ongoing construction of the long-awaited Trans Mountain expansion (TMX), which is expected to start operating late next year.

Yet, oil output is also rising in the province.

“When everything is running, we do have (enough) capacity right now,” said Jason Jaskela, president of Headwater Exploration, a growing junior oil producer.

“The problem is we just have no room for hiccups. There’s just no margin of error.”

The issue of transportation capacity out of Western Canada has been a long-standing concern for the industry and the province.

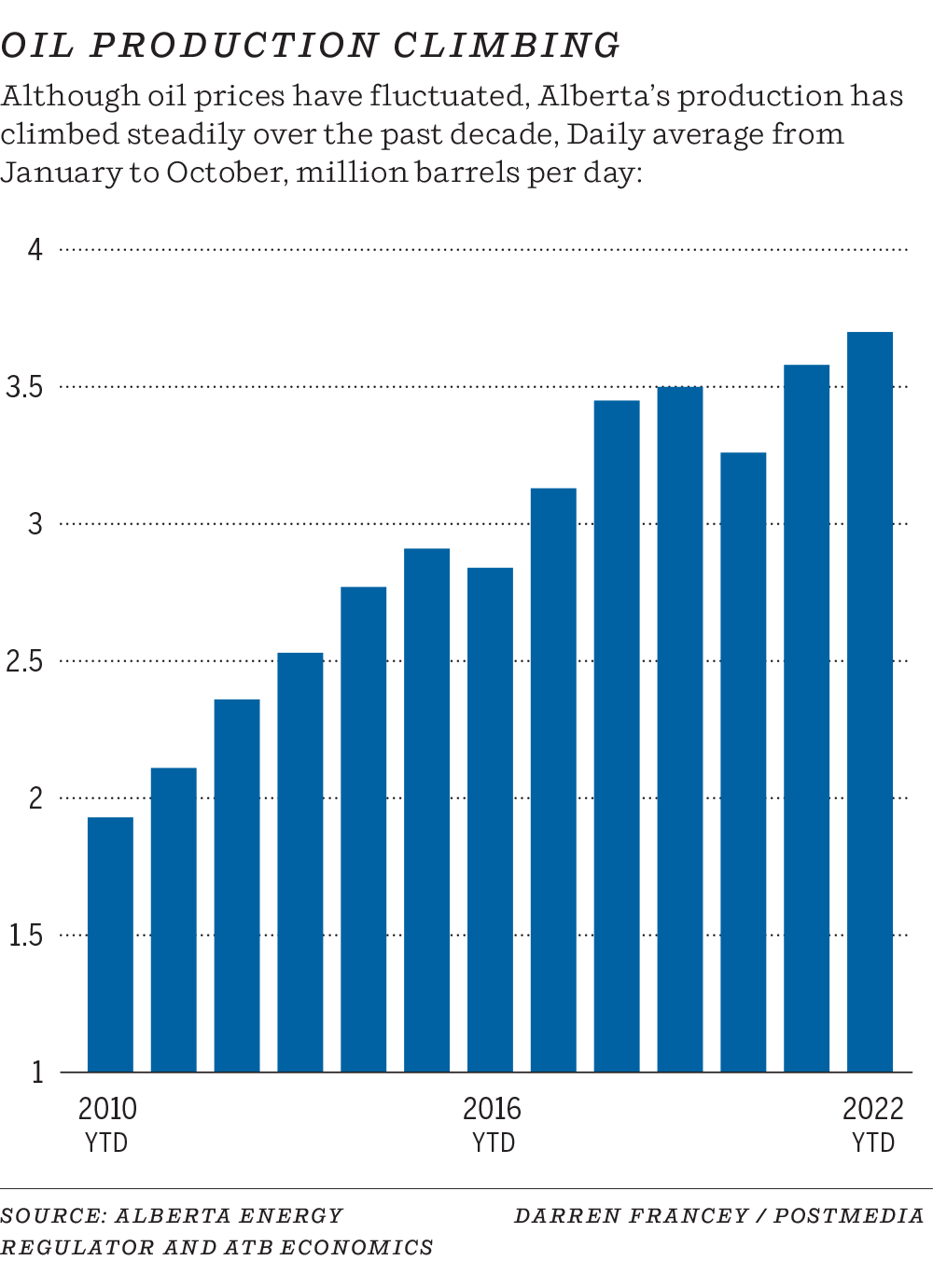

Since 2010, Alberta oil production has risen from nearly two million barrels per day (bpd) to average 3.8 million in October, ATB Financial pointed out in a recent note.

At the same time, it’s been a monumental task to get new pipelines built in the past decade.

The transportation bottleneck came at a cost. Energy consultancy IHS Markit made a conservative estimate that Canadian heavy oil producers lost at least US$14 billion due to a lack of export capacity between 2015 and 2019.

Keystone is a major conduit to send Alberta crude from the Hardisty area into key consuming markets, transporting more than 600,000 barrels per day into the United States.

The cause of the latest spill, with about 14,000 barrels of oil released into a creek in Washington County, Kan., hasn’t been determined. Cleanup work is ongoing.

TC Energy hasn’t said when Keystone will come back online fully, although Bloomberg News reported the Calgary-based company is aiming for a full restart beginning Dec. 20.

“Anytime there is a shutdown of a major artery of that nature, it’s obviously concerning,” Tristan Goodman, head of the Explorers and Producers Association of Canada, said Wednesday.

“It does create anxiety in the industry.”

Recommended from Editorial

-

TC Energy’s troubles mount as Keystone spill remains unexplained after five days

-

Keystone oil spill into Kansas creek is largest in pipeline’s history

-

TC Energy wins approval for NGTL pipeline expansion but shares slide over ballooning Coastal GasLink costs

Pipeline capacity hasn’t been a pressing worry since the start of the pandemic, although the differential has widened this year.

It averaged more than $20 a barrel in October, compared to $12 during the same period in 2021 due to a combination of unplanned refinery outages and the release of heavy oil barrels from the U.S. Strategic Petroleum Reserve, according to the province’s mid-year fiscal update.

The price spread has increased since the spill from $26.30 a barrel to $30 by mid-Wednesday, although it hasn’t gyrated wildly, said Rory Johnston, founder of the Commodity Context newsletter.

“Essentially, there seems to be ample storage capacity in and around Hardisty at the moment,” he said.

“We certainly are not on the razor’s edge of egress capacity as we were back in 2017.”

While producers say the current outage is affecting short-term prices for Canadian heavy oil, they don’t expect it to be a longer-term issue.

“What you’re seeing is there’s just no option for heavy (barrels) to move elsewhere,” said Brian Schmidt, CEO of Tamarack Valley Energy.

“When (the differential) hits $30, you bet that impacts us because a significant portion of our production is heavy.”

With the Trans Mountain expansion in the works, are Canada’s oil pipeline woes finally in the rear-view mirror?

A report by S&P Global this year pointed out the industry finally has some “breathing room,” as the completion of the Trans Mountain expansion and the optimization of existing lines will add a combined 900,000 bpd of pipeline transportation out of Western Canada this decade.

At the same time, it anticipates supply will grow by 715,000 bpd by the end of this decade.

“Despite capacity growth, pipeline adequacy could still become quite tight, making it difficult to manage periods of maintenance or unforeseen operational upsets,” the report cautioned.

“These upsets in the pipeline system go to the need for not having simply adequate western Canadian take-away capacity, but having some surplus in the system,” added Kevin Birn, a vice-president of S&P Commodity Insights in Calgary.

Moving more crude by rail could also be tapped, as such shipments have dropped sharply in the past three years.

Rob Morgan, CEO of privately held Strathcona Resources Ltd., said he is feeling more confident about oil transportation prospects with additional pipeline capacity coming on stream.

The Calgary-based company, through its $2.3-billion acquisition of Serafina Energy earlier this year, moves about one-third of its heavy oil barrels by rail to the U.S. Gulf Coast.

“We are not feeling particularly nervous at this point. We have options . . . and having this rail option is great from a marketing perspective,” he said.

Jaskela expects the price differential will improve next year, averaging around $25 a barrel in the first quarter and $20 throughout 2023. He stressed the key question is how long Keystone remains off-line.

As for the larger issue of Western Canada pipeline capacity, he believes the overarching concern by the industry hasn’t fully disappeared.

“Right now, we’ve got a problem — we have no spare capacity,” he said.

“When TMX comes online, that becomes very, very helpful. But, ultimately, as we see more major projects come into the queue, we will ultimately outgrow that capacity as well.”

Chris Varcoe is a Calgary Herald columnist.

You can read more of the news on source