The Keystone XL project is DOA, with Alberta taxpayers facing more than a $1-billion loss over the province’s investment in the pipeline.

Environmental protests continued this week in Minnesota over construction on Enbridge’s Line 3 replacement project.

And Michigan’s governor is trying to

shut down Enbridge’s existing Line 5

, even though such action would cause fuel prices to spike in the region.

You might think from these developments that additional pipelines aren’t needed and that even existing ones are no longer required.

Yet, a new report by the Canada Energy Regulator (CER) on the country’s pipeline industry over the past five years underscores a critical point.

Oil pipelines in the country have largely been running full since 2015, except in the aftermath of the pandemic, and are still exporting large volumes today.

If production increases in the future — and that depends on many factors, although projections from the province and the regulator have indicated they will — more transportation capacity will be needed, not less.

“What we saw, of course, in the last five years was that no new (oil) pipelines came on stream,” CER chief economist Darren Christie said in an interview earlier this week.

“The report points to the fact that for exports to grow and production to grow, there is going to be some requirement for getting that product to market. And where we stand today, the system is very close to full again, as it was heading into the pandemic.”

The study came out hours before Calgary-based TC Energy and the Alberta government

formally announced they have terminated the Keystone XL development

.

The regulator’s report examines an industry that was often overlooked by the public and media in years gone by, but the clash over Keystone XL — and projects such as Northern Gateway and Energy East — changed that dynamic.

“It used to be that pipelines would go through the regulatory process and no one knew what they were . . . now we know the names of every pipeline out of Western Canada,” says Kevin Birn with energy consultancy IHS Markit.

“This was the flashpoint, the lightning rod, and the (Keystone XL) name is going to be recorded into history.”

Indeed, pipelines have now become central battlegrounds between those who oppose fossil fuel development and those who support it, between policy-makers who want to sideline the industry and those who want to expand it.

“Keystone XL may be cancelled, but the ideas, the opposition, the divisiveness of the name, those issues are not going to end with the cancellation of Keystone XL,” added Birn.

The project’s fate has been sealed since U.S. President Joe Biden nixed the pipeline’s cross-border permits back in January.

The pipeline was first proposed more than a dozen years ago in a much different environment. Construction only began last year after a multibillion-dollar financial commitment from the provincial government, which now estimates taxpayer exposure at $1.3 billion.

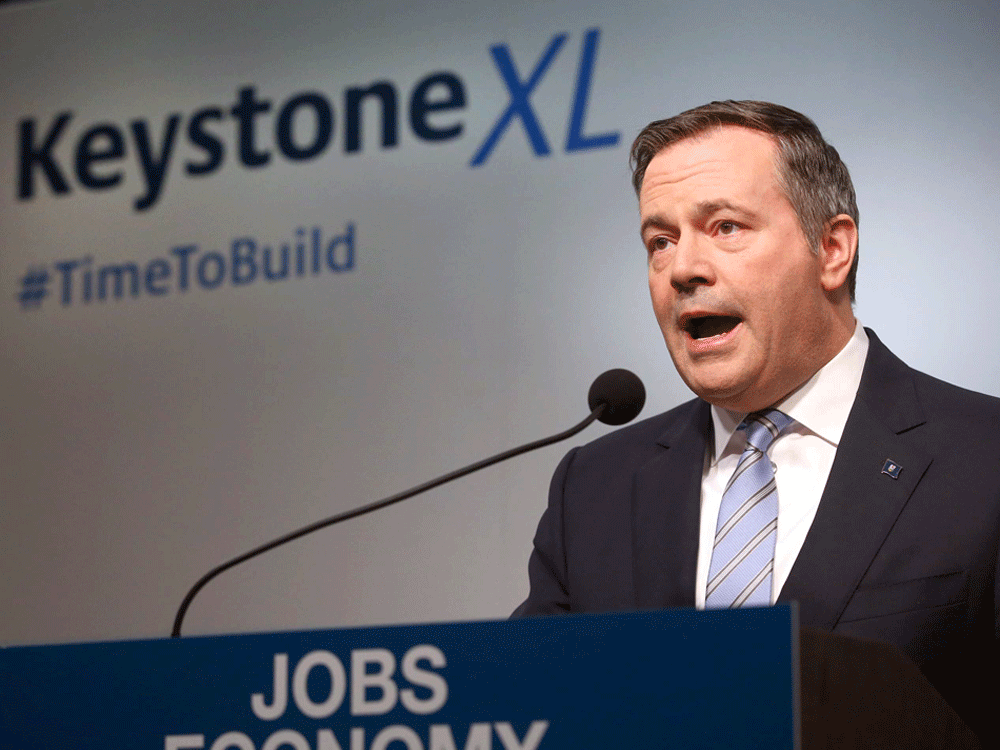

“Jason Kenney desperately wanted a photo op, so he gambled Alberta money and he lost,” NDP Leader Rachel Notley said Thursday.

Notley is critical the UCP invested in a project that the province — and Canada — ultimately had no control over.

Premier Jason Kenney defended the decision and noted his government is examining its legal options, which could include a claim under NAFTA.

“If we are going to have a future for our energy workers, it’s necessary that sometimes the government steps in to de-risk projects that have become too risky in the capital markets,” Kenney told reporters.

“We are confident we’ll be able to reclaim our investment to get damages out of the legal process.”

What are the lessons to be learned from the demise of Keystone XL?

First of all, every pipeline project is going to face increased scrutiny and litigation. The Trans Mountain pipeline expansion and Line 3 development have also faced challenges and are now being built, although the process has taken many years and billions of dollars.

“We all have to be honest about this. There’s no simple answer to pipeline politics,” Notley said in an interview.

“You are always going to be more successful if you are able to engage in it within your own jurisdiction.”

The stakes in the debate are enormous. Canada is the fourth-largest oil producer in the world.

Output increased by 23 per cent between 2015 and 2019 to average 4.9 million barrels per day (bpd) that year.

In a separate study released last fall, the CER projected oil production in Canada will increase by about 18 per cent to 5.8 million barrels per day (bpd) by 2039, before falling to 5.3 million bpd by 2050, under its “evolving energy system” scenario.

That paints a picture of growing Canadian output, although it doesn’t match up with views from some corners that oil demand won’t increase in the coming years as the world decarbonizes.

It’s worth noting that pipeline operators such as Enbridge and TC Energy managed to optimize their networks to add incremental capacity in recent years, said Christie.

However, there clearly was a pipeline bottleneck in late 2018, when supply swamped available space.

The price discount facing Canadian oil soared, costing producers and governments billions of dollars. The province quickly introduced production quotas, which were only lifted last December.

With Line 3 and the Trans Mountain expansion now under construction, those projects will eventually increase pipeline space out of Western Canada by about one million barrels per day.

The question is what happens after that?

“It is going to be a very short window where we’re going to be back up against not having enough capacity,” Canadian Energy Pipeline Association CEO Chris Bloomer said earlier this week.

“We have a huge resource that can continue to be developed and growing in this country. It’s really a question of, ‘Are you going to leave the resource in the ground or are you going to produce it?’ And if you produce it, you are going to need new pipeline capacity.”

Chris Varcoe is a Calgary Herald columnist.

You can read more of the news on source