Alberta will adopt an “agricultural-first” approach when deciding where new renewable energy projects can be built in the province — while creating 35-kilometre buffer zones around “pristine viewscapes” and requiring developers to put up remediation bonds.

For industry proponents, the news feels more like a renewables-second policy. The sector is clamouring for more answers about the potential effect of the new rules on investment into the country’s hottest renewable market.

The province is lifting its moratorium later this week on approving new renewable energy projects and overhauling the criteria for the Alberta Utilities Commission (AUC) to approve future clean energy proposals.

The new policy was announced Wednesday by Premier Danielle Smith and Affordability and Utilities Minister Nathan Neudorf, who said the rules are intended to protect farmland while allowing the renewables industry to grow — although Neudorf acknowledged it will likely slow the sector’s rapid expansion.

“We’re only requesting that the proponent demonstrate the ability for both crops and livestock to coexist on the land for renewables projects. So, we are creating a pathway for this to continue,” he said in an interview.

“We anticipate that there will be some contraction of some of these (proposed) investment projects.”

The UCP government will instruct the AUC to use the new policy direction for approving new projects, beginning March 1.

Changes will not be retroactive, but will apply to 13 projects that began moving through the review process during the seven-month pause, which began in August.

Reaction from the clean energy proponents and developers focused on the lack of specific details on key policies, such as how the province will define pristine viewscapes.

“We still need additional information,” said Canadian Renewable Energy Association CEO Vittoria Bellissimo.

‘All uncertainty is bad uncertainty in this instance’

BluEarth Renewables CEO Grant Arnold said he was pleased to see the changes will not be retroactively applied to projects already built in the province.

However, the Calgary-based company also has about 400 MW of proposed wind and solar developments in the works in Alberta.

“The concepts discussed today by the province, combined, add cost and red tape,” Arnold said.

“I’m not giving the green light on a new project today in Alberta until I have some certainty, and I don’t know if I’ll see it in the near future or in the far future.”

Alberta has seen a surge of wind and solar projects over the past five years.

The province added almost 1.4 gigawatts (GW) of installed renewable capacity in 2022 — about three-quarters of all such additions across the country — and the percentage topped 90 per cent last year.

With the changes, renewable projects will no longer be allowed on what the province considers Class 1 and 2 farmland under a land suitability rating system — covering about seven million hectares out of 26 million hectares — unless the proponent shows livestock or crops can coexist on the site, Neudorf said.

The province will also look to create tools to ensure native grassland, irrigable land and productive farmland will continue to be available for agriculture.

“We’re trying to be responsible with not just one industry, but many industries,” the minister said.

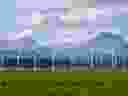

Buffer zones extending at least 35 kilometres will be created around protected areas and what the province designates as pristine viewscapes, such as the Rocky Mountains or the foothills.

In those areas, wind farms with turbines will be a “no-go,” said Neudorf. Other developments in the zone could require the AUC to conduct a visual impact assessment.

-

Alberta renewables sector fears politicization of energy as moratorium ends

Alberta renewables sector fears politicization of energy as moratorium ends -

Renewables pause in Alberta affecting 118 projects worth $33 billion, think tank says

Renewables pause in Alberta affecting 118 projects worth $33 billion, think tank says -

Southern Alberta municipalities receive substantial revenue from renewable energy projects

Southern Alberta municipalities receive substantial revenue from renewable energy projects

The minister doesn’t anticipate many projects will be affected, but the Pembina Institute said it appears the buffer zone could cover up to 76 per cent of southern Alberta due to protected areas in place.

“If the government is interested in agriculture-first, these rules should apply to the oil and gas sector, to residential and industrial development,” said Simon Dyer of the Pembina Institute.

The province said protected areas will focus on the western portion of Alberta and haven’t been established yet.

The new policy will also create guidelines around reclamation costs to pay for the cleanup once a renewable project reaches the end of its life, such as putting up a bond to cover those expenses.

The money will either be given to the AUC or negotiated with the landowner, but the specific amount required has not yet been set.

The incoming changes will give municipalities the automatic right to participate in AUC hearings on new projects. Other parts of a broader government review of the electricity sector are also being developed and expected to be revealed later in March.

Controversy over Alberta renewables policies unlikely to abate

The new policy will likely continue to stir the controversy that has surrounded Alberta’s pause, which was adopted last summer amid a growing lineup of proposals before the AUC.

Alberta has excellent wind and solar resources and, as Canada’s only deregulated power market, it has become a magnet for private-sector investment. The energy-only market allows developers to build projects and sell the electricity, along with renewable energy credits, to corporate customers through power purchase agreements.

The Business Renewables Centre Canada said corporate-based PPAs have garnered more than $6.4 billion in investment since 2019.

Greengate Power CEO Dan Balaban, which developed the largest solar project in the country south of Calgary, said Wednesday there is still uncertainty and some subjectivity in how the new rules will be applied.

His company, which has been involved in renewable development in Alberta for more than a decade, has seen the province become Canada’s top investment destination for wind and solar, which is “a modern miracle to see that happen in oil country.

“I am a little disappointed, I’d say, that it looks like that pace of growth is not going to continue,” Balaban added.

“It certainly seems like they’re prioritizing agriculture over renewables — agriculture-first would imply that … I think both can coexist.”

However, the review tackled issues that needed a deeper examination due to the industry’s speedy expansion, said Rural Municipalities of Alberta president Paul McLauchlin.

“This is actually not that limiting,” he said.

“Most of rural Alberta should be happy with the path forward.”

Chris Varcoe is a Calgary Herald columnist.

You can read more of the news on source