An energy crunch in Europe, exacerbated by the escalating conflict in Ukraine, is breathing new life into hopes that Canada’s Atlantic provinces could become a hub for natural gas exports, industry watchers say.

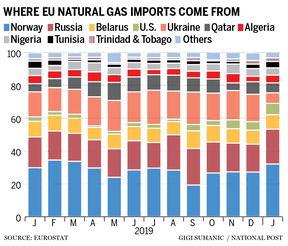

The energy starved European Union sources almost 40 per cent of its natural gas from Russia, much of it flowing through Ukraine. As a result of shortages last year, natural gas benchmark prices in Europe more than tripled, with the spot price at one point soaring to more than 10 times its North American counterpart.

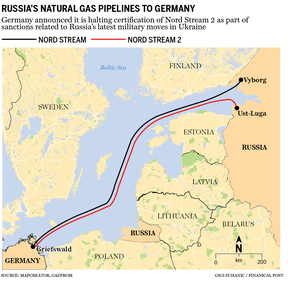

Russia’s move into Eastern Ukraine this week has only added more uncertainty: The German government on Tuesday announced that it was halting the approval process for the Nord Stream 2 project, a controversial twinning of a major pipeline bringing Russian gas to Germany under the Baltic Sea that might have alleviated some of the supply concerns.

As Europe’s gas woes mount, at least two companies are exploring LNG options on Canada’s East Coast.

Earlier this month, Spanish oil major Repsol S.A. was reported to be considering converting its Saint John LNG import terminal into an export facility. And in Nova Scotia, Calgary-based Pieridae Energy Ltd. already has plans to build a floating LNG export terminal in the town of Goldboro, with an annual capacity of about 10.2 million tonnes.

Pieridae Energy director of external relations James Millar told The Financial Post in an interview that the possible shift to exports by Repsol is well-timed. He said that while Europe’s gas supply problems have been thrust into the spotlight by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, their roots are structural and will continue regardless of the outcome of the conflict.

“Somehow this will be resolved,” said Millar of the Ukraine crisis. “And then you may not see as much focus on it (LNG supply to Europe) for a few years, but if you don’t deal with your security of supply issue, you could see a scenario like that happening again…. So, a Canadian solution makes a lot of sense.”

Saint John LNG, previously known as Canaport, opened in 2009 and was co-owned by Repsol and Irving Oil Ltd. until November, when Repsol bought out Irving’s 25 per cent stake and renamed the facility.

“Repsol is continuously exploring options to maximize the value of the terminal, with a particular focus on new lower-carbon opportunities to help meet market demand and to support the energy transition,” Repsol legal counsel and spokesperson Michael Blackier told The Financial Post in an email. “The company will look at any/all business that enhances or creates value at Saint John LNG.”

According to a Bloomberg News report in the trade publication Gas Processing and LNG, Repsol has filed a not-yet-public description of the project with the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency, describing its development plans. Saint John LNG already holds an export permit that it filed for in 2015 and received in 2016, which could speed the regulatory process.

Saint John LNG is a land-based facility, meaning the infrastructure to regasify the natural gas is located on-shore. Pieridae’s Millar said that if Repsol does pursue exports, he suspects the company could do it via a floating terminal because infrastructure of that type can be installed more quickly and has less of an impact on the terrestrial environment.

Pieridae has announced similar plans in Goldboro after cancelling a stillborn attempt to build a land-based facility last summer due to cost issues. The company proposed the floating terminal in January of this year in response to rising gas prices in Europe, and it plans to offset emissions via a carbon sequestration project in Alberta.

The EU, meanwhile, has in recent years begun to diversify its gas sourcing via other pipelines, such as the TurkStream pipe, which runs under the Black Sea. But Western sanctions on Russia could imperil supplies from even the routes that sidestep Ukraine.

And demand in Europe looks set to rise. Germany, for example, has pledged to decommission all of its nuclear power plants by next year and phase out coal-fire electricity by 2030. And earlier this month, the European Commission, which is the EU’s executive branch, officially endorsed gas as a transition fuel on the way to a lower carbon economy.

Some of the additional demand can be met by Qatar — which Millar described as one of Canada’s main competitors for the European market — but it is unclear what the limits on that country’s export capacity are. Qatar is the world’s third-largest producer of natural gas and Canada is the fourth.

“It was always predicted, irrespective of the current Ukraine issue, that demand in Europe will continue to grow,” said Paul Barnes, director for Atlantic Canada and the Arctic at the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, or CAPP.

“Around the Mediterranean, and India in particular, will need a lot of natural gas, some of which they really don’t want to depend on Russia for, so they’re looking for other sources.”

Millar added that Canada has a competitive advantage over the United States because a tanker travelling from Nova Scotia to Europe will take about six days less than one travelling from the United States’ Gulf Coast, where much of the country’s export capacity is located.

“That’s one point we’ve mentioned the last few years,” said Millar. “You have that shipping advantage of being able to get the product there quicker than from Texas of Qatar.”

(Atlantic Canada) has the potential to become an LNG hub

Paul Barnes

For both Pieridae’s Goldboro terminal and Saint John LNG, the natural gas would likely come from Western Canada. Miller said the most direct way to transport gas to the Atlantic provinces is to use the TransCanada Mainline pipe through central Canada, followed by the Trans Québec & Maritimes Pipeline and the Portland Natural Gas Transmission System, taking a shortcut through Maine, before switching to the Maritimes and Northeast Pipeline for the final leg of the journey.

But according to Miller, that plan could strain TransCanada’s capacity and require owner TC Energy to either increase back-pressure on the pipe or “loop” it — a term used to describe laying a parallel pipe in the same ditch. Miller spent nine years working for TC Energy before he joined Pieridae.

Canada currently has no LNG export terminals on either coast, thanks in part to a regulatory environment that often delays projects for years.

Last year, Chevron Canada Ltd. sold its stake in a planned export terminal in Kitimat, B.C. that is slated to export 18 million tonnes of LNG annually, after more than a decade of little progress. And construction on Shell’s LNG Canada terminal in the same town is now more than half finished, but that has also taken over a decade. Pieridae’s Goldboro terminal has likewise been in the planning stages since 2012.

“(Atlantic Canada) has the potential to become an LNG hub,” said Barnes. “It’s just that they don’t really have facilities at the moment that can take that gas and get it to market, but the potential is certainly there.

“And as technology improves and as the cost of gas increases … and the industry worldwide is moving away from heavy hydrocarbons like coal and oil into more gas and renewables, natural gas potential in Atlantic Canada becomes a much greater reality today than in recent times.”

You can read more of the news on source