Canada is often described as the best place to look for the immeasurable amounts of copper, nickel, lithium and other metals that will be needed to build the electric vehicles of the future. Known deposits litter the country, and there are no shortage of miners with the wherewithal to pull them out of the ground.

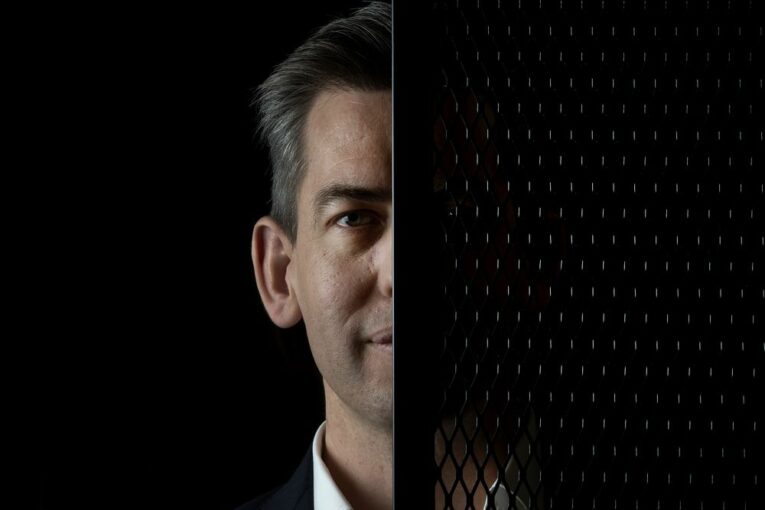

But Tim Johnston, a 36-year-old serial entrepreneur, who spent a decade advising the largest mining companies in the world, spotted a totally different, untapped source for metals: recycling.

Canada’s mining companies have struggled over the past five years to bring on new supplies of metals. They are beset by fundraising challenges, local opposition to new mines, construction mishaps, and the extremely long odds in finding rich metal deposits hidden beneath the earth’s surface. Johnston, executive chairman and co-founder of Toronto-based Li-Cycle Holdings Corp., bypassed all of that by deciding to tap into the green transition by creating a recycling company. Li-Cycle is now well on its way to erecting one of the most significant new sources of copper, nickel and lithium in North America.

Already, Li-Cycle has raised more than US$700 million since it was founded in 2016 and devised and patented a process to extract metals from old earbuds and other electronic waste, including end-of-life batteries. It also has announced or started construction on eight facilities in four countries, and struck deals with General Motors Co. and South Korean battery manufacturer LG Chem Ltd.

“We can produce the materials cheaper than what they can mine them for,” Johnston said in an interview. “We can refine them cheaper than they can refine them.”

We can produce the materials cheaper than what they can mine them for

Tim Johnston

Johnston noted that the majority of lead in the lead-acid batteries found in conventional vehicles is recycled. “If you fast forward 20 years … I don’t see any reason why, we can’t be approaching 75 to 80 per cent recycled material” in the electric-vehicle (EV) battery supply chain, he added.

That recycling, not mining, could end up providing much of the raw materials for the solar panels, wind turbines, and EV batteries represents an unexpected twist in the energy transition. The traditional mining and exploration industry is far larger, yet in recent years it has come up with few new nickel, lithium and cobalt mines in the world, let alone North America.

Although it’s clear that recycling alone won’t be able to meet the onslaught of demand coming for battery metals as EV adoption increases, it is nonetheless clear that recycling will make a significant contribution. Li-Cycle alone may supply feedstock for 15 per cent of North America’s projected battery manufacturing capacity by 2025, according to estimates by analysts at Cowen Inc., an investment bank.

That’s based on the Cowen analysts’ expectations that Li-Cycle will be able to refine at least 220,000 tonnes of lithium-ion battery equivalent material per year at its hubs by 2025 — enough to produce roughly 24,000 tonnes of nickel, 3,500 tonnes of cobalt, and 20,000 tonnes of lithium carbonate annually.

That may be optimistic given that the company has only announced one hub refinery, currently under construction, capable of processing less than half of that amount of material.

The company also faces no shortage of challenges, particularly in the area of its governance, as demonstrated by a recent report by short seller Blue Orca Capital. The report noted that the British Columbia Securities Commission recently upheld a decision by the TSX Venture Exchange that requires Johnston to seek permission from the exchange to serve as a director at any of its listed companies. That decision stems from his failure to fully disclose a $1-million discount on a past fundraising of $5 million while chief executive in 2018 and 2019 of Desert Lion Energy Inc.

Johnston said he relied on legal counsel, and also was focused on the company’s operations at the time, as it was on the brink of insolvency. But the short report also noted that Li-Cycle purchased $86,000 worth of leather from a business with connections to the family of co-founder and chief executive Ajay Kochhar. Blue Orca also took issue with the company’s accounting procedures, comparing them to Enron.

“Rather than responding with a point-by-point rebuttal that would give these accusations more weight than deserved, we remain focused on our mission and best serving our customers and partners,” Johnston wrote in an emailed statement about Blue Orca’s report.

Johnston added that the company’s accounting procedures, including its revenue recognition process, are all outlined and disclosed in its financial statements. Still, the company’s stock, which trades on the New York Stock Exchange, has declined by about 33 per cent since the start of the year, to about US$6.75 per share as of April 28.

Despite those and other challenges, Li-Cycle remains on track to build facilities that could contribute significant quantities of battery metals as soon as 2023.

To put that into perspective against mining, out of hundreds of companies searching for critical minerals over the past half-decade listed on the TSX Venture Exchange, the traditional centre of mining exploration finance, few, if any, have advanced to production in Canada or elsewhere in North America.

In 2018, Nemaska Lithium Inc., for example, announced it had raised $1.1 billion for a mine and electrochemical plant in Quebec with estimated annual production of roughly 35,000 tonnes of either lithium carbonate or lithium hydroxide, subject to market factors. But after hundreds of millions of dollars in construction cost overruns, in 2019, Nemaska filed for bankruptcy protection. In 2020, Investissement Quebec and other investors took the company private, but have said nothing about whether production has started.

First-mover advantage

A number of rivals have emerged to compete with Li-Cycle in the battery recycling market. They include Nevada-based Redwoods Materials, founded by J.B. Straubel, Tesla Inc.’s former chief technical officer; incumbent chemical companies such as Germany’s BASF SE; and upstart exploration companies pivoting away from mining, such as Toronto-based Electra Battery Materials Corp., formerly First Cobalt Corp.

Analysts said the nascent state of the field make it difficult to predict the precise amount of metals recycling can supply, analysts said, but Li-Cycle told shareholders last year it controls 30 per cent of the recycling market in North America.

“Li-Cycle has a first-mover advantage in the North American lithium-ion battery recycling market,” Jeffrey Osborne, an analyst at Cowen, wrote in a note earlier this year, adding that recycling “helps reduce the risk of millions of tons of spent batteries reaching landfills.”

Under its hub-and-spoke model, Li-Cycle has announced plans to build “spoke” facilities in Arizona, Alabama, Ohio, Germany and Norway, at a cost of roughly US$10 million each, where it can collect old laptops, earbuds, and other electronic waste, and shred it to produce a fine dark powder, known as “black mass.”

Li-Cycle already operates two such spokes in Kingston, Ont. and just outside Rochester, New York, which are expected to produce about 7,000 tonnes of black mass in 2022.

It is building its first “hub” facility, at a cost of US$500 million, next to its spoke in New York, so it can refine the black mass into the chemical building blocks of electric vehicle batteries — nickel sulphate, cobalt sulphate and lithium carbonate. The hub is scheduled to begin operating in 2023.

Analysts expect Li-Cycle to announce an additional 12 spokes and three hubs by 2024 — a furious pace that will require Johnston and Kochhar to hire and train hundreds of people, steer multiple projects through permitting and construction, while still striking deals with automakers and battery manufacturers for future recycling feedstock.

In the first quarter, it produced US$3.8 million in revenue, less than analysts expectations of US$7 million.

Johnston said it is still too early for the company to even issue guidance, so they just try to help manage analysts’ expectations.

“We’re focusing on the build out of our spoke network, on the build out of the hub, the capital costs, those sorts of things,” he said.

Help from Koch

In one sign that even Johnston thinks the company’s expansion plans are ambitious, Li-Cycle last year took a $100-million investment and struck a partnership with a subsidiary of Koch Industries, the industrial conglomerate overseen by chairman Charles Koch, a staunch opponent of environmental regulation. The Koch subsidiary will help supply equipment and assist with “operational readiness,” like hiring and training employees.

The partnership with Koch, in combination with Johnston’s decade long career at Hatch Ltd., where he and Kochhar helped the largest mining companies in the world build projects, form a stark contrast with the ‘green’ reputation that Li-Cycle promotes as a recycling company. But it shows that the energy transition is not always black and white, with environmentalists on one side, and traditional resource companies on the other.

Rather, Johnston is on both sides, having spawned a wide range of enterprises at the forefront of the green transition since 2016 including Li-Cycle, and also Li-Metal Corp., which last year raised $32 million on the Canadian Securities Exchange to develop a recycling process for lithium metal, a key component in the anodes of next generation solid-state batteries.

Johnston said he and Kochhar also founded an airbag recycling business based in Markham, Ont.; and Johnston helped found Blue Horizon, an exchange traded fund on the New York Stock Exchange, which is indexed to 100 companies involved in the energy transition. Not all have thrived; indeed some have failed, but Johnston continues to push forward.

Maciej Jastrzebski, another former Hatch consultant who is a co-founder and CEO of Li-Metal, described Johnston as keenly attuned to opportunities created by the “industrial energy revolution” away from fossil fuels.

“Often the best place to work is where there’s a clear problem that nobody else has seen,” said Jastrzebski, “and Tim is just profoundly good at spotting those.”

Under water

Kochhar said that he and Johnston worked on a battery recycling project while at Hatch, and walked away convinced it was ripe for innovation.

“A lot of the groups before us have basically burned off what (metals) they don’t want,” Kochhar told the Financial Post last year.

But Kochhar said burning releases fluorine or “forever chemicals” into the atmosphere and is not very efficient. Automakers were also concerned about the safety of such processes as the voltage of batteries grows higher and higher.

In 2016, Johnston and Kochhar, having both left their jobs at Hatch, devised a new idea: Shredding old battery scrap and electronic waste while submerged in a water-based solution.

The plastic casing naturally floats to the top, while denser copper and aluminum foils and the so-called black mass, which contains cobalt, lithium and nickel, settles. Because it’s in solution, emissions are nil, and there is also a lesser chance of explosion, they said.

Li-Cycle’s process is also more efficient, recovering 95 per cent of the metals compared with a 50 per cent industry average, according to Brian Dobson, an analyst at the Boston-based Chardan Research.

As battery metal prices rise, that efficiency translates to real money: lithium carbonate has spiked 800 per cent since October 2020, from US$5,865 per tonne to an all-time high in February of US$52,634, according to Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, a pricing company.

George Miller, a senior analyst at Benchmark, said most lithium either comes from a mine or from giant chemical brine ponds, mainly located in the South American desert. But as EV demand has taken off, new lithium supply has been “slow to wake up,” creating huge price volatility.

“This is a new era of lithium pricing,” Miller said. “I see no fundamental reason why the prices would fall for some time.”

Dobson estimates Li-Cycle could hit US$299 million in revenue in 2023, and US$226 million in net income by 2025.

Ironically, one of the risks it faces is that battery manufacturing becomes more efficient because today, much of its feedstock comes from scrap metal produced by inefficiencies at battery manufacturing plants.

That’s in part why South Korea’s LG invested $50 million in Li-Cycle in December 2021 and struck a deal to supply battery scrap for ten years, which Li-Cycle would recycle and sell back. The contract is for enough nickel sulphate for 300,000 electric vehicles.

As part of that deal, Li-Cycle will build a “spoke” facility for Ultium — a GM and LG joint venture — at its battery manufacturing plant in Lordstown, Ohio.

Catches COVID

It is one of a half-dozen deals that Li-Cycle has announced since the pandemic began.

“I tried not to let COVID slow me down,” said Johnston, who said Li-Cycle was three years into its plan in March 2020, and did not want to risk losing its first-mover advantage.

As he explained it, Li-Cycle’s business is predicated on the “network effect,” in that the more infrastructure it builds, the more its efficiency grows.

So Johnston said he kept travelling, spending at least half the week on the road, often taking plane trips. Mainly, he drove his Tesla Model S around Lake Ontario to the company’s spokes in Kingston and Rochester.

“I got to know the border guards really well,” he said.

But after dodging COVID-19 for nearly two years, the virus finally caught up with him in January, just six weeks after his baby daughter was born. It started with a fever, and soon transitioned into “crazy hallucinations” of shredding machines, eventually infecting the entire family.

Johnston said it took weeks before he lost his cough and could move around easily, and yet he kept hopping on board calls, and attending meetings.

Today, Li-Cycle has an entire floor of prime office space in downtown Toronto, located just on the edge of Lake Ontario, with a view of planes taking off from Billy Bishop Airport.

On a visit earlier this year, the office was essentially empty, except for a dozen or so employees, and yet Johnston said that was all part of the plan: he’s banking on rapid expansion.

The company still faces many tests, including managing its projects and meeting profit expectations. And as more operations come online, it remains to be seen whether its water use, noise levels and other impacts will be as minimal as the company promises.

But so far, of the dozens of companies that formed in the last half-decade with designs on supplying raw materials for a North America battery supply chain, Li-Cycle looks to be one of the only ones that may deliver metals anytime soon.

“You can either be the smartest, you can cheat, or you can be first,” said Johnston. “We were first.”

• Email: [email protected] | Twitter: GabeFriedz

You can read more of the news on source