When I was five years old, like many kids that age, I was obsessed with trains.

Many a Saturday morning was spent with my father and brother down at Toronto’s Cherry Street railway bridge beneath the switching tower, watching passenger trains come and go from Union Station.

So intense was my obsession that my dad even made me mixtapes of songs about trains (this was 1985, before CDs appeared).

One of those tapes had three Gordon Lightfoot songs with locomotive references: “Steel Rail Blues,” “Early Morning Rain,” and “Sixteen Miles (To Seven Lakes).”

I must have listened to that tape hundreds of times while falling asleep at night, and I can only assume that the stories in those songs, and the voice of the man singing them, worked their way deep into my unconscious mind.

As I grew up, I became aware that this voice was the same one often coming from the radio or my dad’s record player, filling the air with beautiful melodies and words that somehow spoke to me, even if I didn’t fully understand them.

Over time, it began to occur to me that many of the songs were about where we lived: the Great Lakes, maritime waters, rivers, streams, forests, mountains, autumn hills and even my hometown of Toronto. The way the words and the melodies weaved together seemed to paint pictures of the Canadian landscape like no other music did.

The songs were about us, too: miners, truckers, sailors, rich men, poor men, old soldiers, down and out ladies, fortune tellers and lovers, lost and won.

Lightfoot had that rare gift of being able to take the struggles, triumphs and emotions of people from all walks of life — our stories — and articulate them in a relatable way with a voice that, at its peak, was unmatched in popular music, in my humble opinion.

His was a voice that just seemed to always be there, accompanying us through life, a source of comfort, and, in the tradition of all great troubadours, teaching us lessons about the hubris of humankind.

Consider the captain of the American steamship Yarmouth Castle, who left in a lifeboat as the ship burned with 87 passengers still on board while en route from Miami to Nassau in 1965. Lightfoot wrote about the disaster, still one of the worst in North American waters, in his 1969 masterpiece “Ballad of Yarmouth Castle.”

Or recall the tanks ordered by U.S. president Lyndon Johnson to go rolling in against Black demonstrators during the Detroit riot in the summer of 1967, resulting in 43 deaths and more than 1,000 injuries. The riots were chronicled by Lightfoot the following year in “Black Day in July,” a song that was banned by several U.S. radio stations for being too controversial.

Picking up the guitar as a teenager, I was immediately drawn to Lightfoot’s intricate fingerpicking style, the rhythmic, pulsating strumming of that signature, booming Gibson 12-string and his deceptively simple arrangements adorned by always talented sidemen. I voraciously learned as many songs as I could.

Then there were the lyrics. Oh, the lyrics.

The Canadian writer Peter C. Newman once told me that he believed Lightfoot was, at heart, a poet. I’m inclined to agree.

Reading the lyrics of Lightfoot’s songs, one realizes that even if he hadn’t put them to music, they stand as brilliant works of poetry on their own.

Take this line from the 1976 chart-topper “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald”:

I could go on. But you get the picture.

Listening to how Lightfoot married these words rich with imagery and feeling to equally beautiful and original melody lines was a revelation, at least to my teenage brain.

Now in the mid-1990s, when I was in high school, Gordon Lightfoot wasn’t exactly considered cool. I often wonder where all the fans who are my age now were when I seemed to be the youngest person lining up outside Massey Hall in 1998.

It wasn’t until the year 2000 when I stumbled upon an internet discussion group of Lightfoot devotees — many my age — from around the world that I found my kindred spirits. The next year, a convention organized by Connecticut fan Jenney Rivard brought more than 60 of these fans to Toronto from as far away as Austria, England, Ireland, Australia and the United States, for Lightfoot’s four-night Massey Hall residency. One afternoon, we all found ourselves at the home of Whitby fan Charlene Westbrook, profiled in the Star by my colleague Amy Dempsey in 2014, for a barbecue. Inevitably, the guitars came out and people from around the world who had scarcely known each other a few days before started singing Lightfoot songs for hours into the wee hours without missing a beat. Many lifelong friendships were forged that night.

It was a microcosm of the crowds that gathered at Massey Hall or wherever in the world Lightfoot played, and a testament to his unique ability to sing and write about where he was from and simultaneously achieve mass appeal.

Before CanCon rules dictated in 1971 that 30 per cent of radio airplay here be devoted to Canadian music, Lightfoot managed to find the sweet spot between singing about our hard-scrabble land with the trials and tribulations we all face, and commercial success, especially south of the border. He arrived in the mid-1960s when a national cultural identity was burgeoning in Canada and he found a way to incorporate what many felt into voice and song, without being boastful.

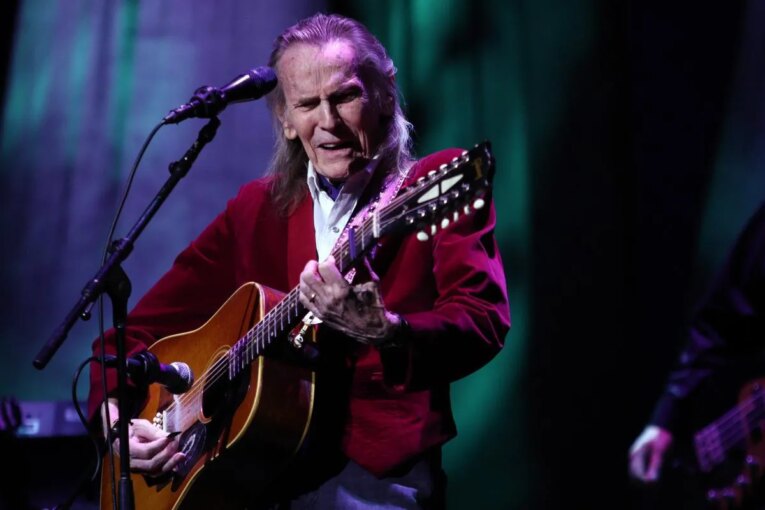

Indeed, it was Lightfoot’s reserved disposition and shyness that endeared him to many fans. (He was never known for his onstage banter; the songs do the talking.) His stage show was free of artifice and gimmickry generally; just a man and his guitar tastefully backed by band of top-tier musicians. The audience always got the straight goods.

He was one of us, a small-town kid who conquered one of the planet’s most competitive businesses, and unlike many of his Canadian contemporaries such as Neil Young and Joni Mitchell, Lightfoot stayed in this country.

When the song “Sundown” and album of the same name simultaneously made it to No. 1 on both the U.S. Billboard singles and album charts in the summer of 1974, Lightfoot was quietly managing his career from Toronto, his home since the early 1960s.

Here was a guy from Orillia who sang about the Rocky Mountains, the Plains of Abraham, Yonge Street, Georgian Bay and the building of the Canadian Pacific Railroad, as well as the universal themes of love and regret, and was adored by millions around the world for it.

In doing so, he proved for countless Canadian artists to come that you could make it as a pop star without having to live in New York or Los Angeles.

“He sent the message to the world that we’re not just a bunch of lumberjacks and hockey players up here. We’re capable of sensitivity and poetry and that was a message that was delivered by the success of Gordon Lightfoot internationally. People were more willing to listen to someone from Canada because someone of such enormous talent had paved the way,” says Rush’s Geddy Lee in the 2019 documentary “Gordon Lightfoot: If You Could Read My Mind,” directed by Martha Kehoe and Joan Tosoni.

When Massey Hall’s long-overdue renovations finally came to an end in the fall of 2021, the only natural choice to reopen the 128-year-old Grand Old Lady of Shuter Street was the man who since 1967 performed at the venue more than 170 times, the most of any popular artist. (Lightfoot had also closed the iconic venue down in the summer of 2018 before its three-year makeover.)

In one of those strange ways that life has of coming full circle, I managed to get tickets to opening night and took my 75-year-old dad, who got me started on Lightfoot in the first place. We had the pleasure of seeing then-mayor John Tory present the key to the city to the songwriter and declare Nov. 25 Gordon Lightfoot Day in the city.

Opening for Lightfoot was his old friend, the American folk singer Tom Rush. In another uncanny coincidence, my dad had included one of Rush’s train songs, “The Panama Limited,” on the same mixtape from my childhood with the Lightfoot tunes. There were goosebumps.

Then, in what was more of a love-in than a concert, for an hour and 15 minutes Lightfoot played us the carefully crafted songs that had become the soundtrack of our lives — tales about riding the rails, a soldier returned from war, life on the road, the triumphs and defeats of personal relationships, a shipwreck, the longing for the hands of a lover on a long winter’s night, and the pain of being stuck in the grass in the early morning rain, homesick for the ones we love.

To be sure, the face was gaunt, the voice weathered, betraying the toll of years of touring and the bottle. But the emotion, sensitivity and musicianship were still there. At 83, he retained the ability to reflect our collective experiences and make you feel as though he was singing especially for you in a living room full of friends.

We shall not see the likes of Gordon Lightfoot again. But the music he gave us — our music — will play on.

does not endorse these opinions.

You can read more of the news on source