“People who need people are the luckiest people in the world,” goes the song sung by Barbra Streisand in the 1963 musical Funny Girl .

It is unlikely anyone in oilfield service (OFS) is feeling particularly fortunate, but at least the personnel issue has switched from a surplus to shortage: hiring not firing. The challenge is now persuading those laid off since late 2014 to consider coming back.

The problem is clearly acute when Calfrac Well Services is running radio ads. In mid-June, an FM station aired a commercial about an upcoming job fair in Calgary. Calfrac needed Class 1 drivers with a clean record to drive their frac fleets to jobs. Calfrac clearly has more work lined up after road bans come off than they have people to do it.

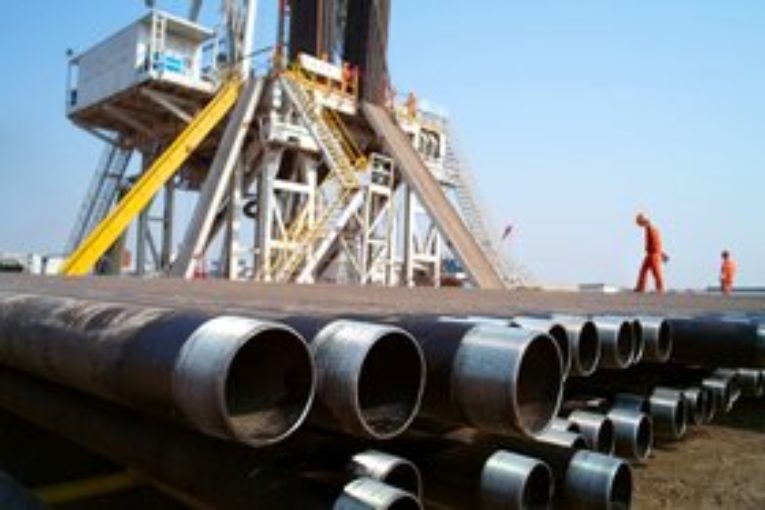

Once you start looking, all the larger OFS outfits in drilling, completion, workover and related services need people. On the job site Indeed, enter any of the bigger names—Precision, Ensign, Trican, Secure, Trinidad, Savanna, CWC—and you’ll find job postings for every field and support operational position in the company. Some are looking for complete crews for service rigs that clearly haven’t worked in a while. Others need drivers and heavy-duty mechanics. Mullen’s heavy crude hauling division requires subcontract tank trucks with drivers, meaning it doesn’t have enough of either.

There’s obviously something going on out there. Virtually all OFS companies kept downsizing through 2015 and 2016 in a desperate attempt to match expenses with revenue. Wages were cut for the survivors. Judging by all the red ink and debt covenant defaults, this was not entirely successful. But those who are hiring today protected their companies and balance sheets sufficiently enough that, when the phone rang, they could go to work. Maybe. If they only had enough people.

Persuading the formerly employed to come back to the industry that treated them so well for so long then fired them is turning out to be a major challenge. Most field personnel are in the 18–50-year-old range. These are the years of high financial needs requiring steady income. That’s when you buy a vehicle, get married, have kids and, if you save enough money, buy a house. Each of these commitments requires regular and predictable paydays.

Read more: David Yager writes a monthly column for Oilweek.

So when you lose your oilpatch job, you don’t have the luxury of waiting for the phone to ring. Unlike some in a senior white-collar position who might get enough money to live for a while on the way out the door, the severance package for the working patch is the statutory minimum. For hourly employees, it will only be holiday pay. These people can’t wait a year or more to go back to work. The majority must find some income within weeks. Many lost their houses. Everyone lost their dignity.

And when there are mouths to feed and payments to make, it really doesn’t matter what the job is. When the new Lowes building supply store opened in Calgary, a floor sales rep was an experienced oilfield surveyor and the cashier a geological technician. They had to eat. Be assured this story has been repeated thousands of times across the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin by displaced oil workers who had to find something to keep the lights on.

So the patch calls them back. Now what?

Problem one is neither activity nor oil prices have stabilized enough for employers to make long-term employment or compensation commitments. Even with the Petroleum Services Association of Canada and the Canadian Association of Oilwell Drilling Contractors both increasing their drilling forecasts for the rest of the year, uncertainty remains. However, some companies have visibility to the end of the year, which is big improvement when recruiting.

Problem two is most positions are now paying less. Compensation has been cut and, while customers are reluctantly accepting some price increases to crew the equipment, OFS employers have a long way to go in terms of acceptable profitability. This puts a cap on wages. But some service companies have negotiated price increases sufficient to make guaranteed compensation commitments to get the people they need.

Problem three is relentless media reports about how oil has no future. Electric cars. Peak consumption. Flat prices. Fleeing investment. Perpetual pipeline opposition. You lost your oilpatch job and an incredible number of people publicly believe the world is better for it.

Hardly compelling, is it?

That said, one of the most dynamic characteristics of OFS in good times and bad is somehow this industry finds the personnel to get the job done. And it will again. It just remains more challenging than it ought to be.

You can read more of the news on source