Consumers and businesses in the Maritimes already have the highest natural gas bills in the country and that’s not likely to get better anytime soon due to an increasingly unsettled East Coast energy sector.

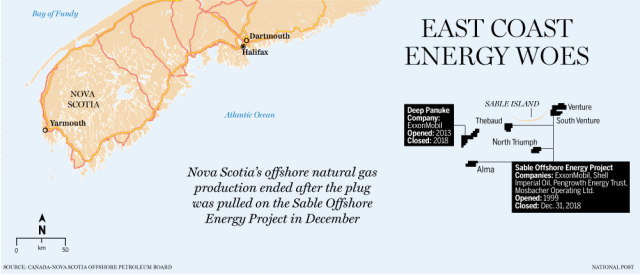

At the centre of the current unease is the shuttering of Nova Scotia’s offshore natural gas production after the plug was pulled on the Sable Offshore Energy Project, some 200 kilometres into the Atlantic Ocean, in December.

Sable, which began production in 1999, provided a domestic source of natural gas and delivered $1.9 billion in royalties to the Nova Scotia government during its lifespan.

There is a significant threat to natural gas users with the traditional supply of natural gas ending,

Colleen Mitchell, president of the Atlantica Centre for Energy

The plant’s closure, by operator ExxonMobil Canada Ltd., was preceded by the loss of Encana Corp.’s Deep Panuke Offshore Gas Project, which was capped in May 2018. Production at Deep Panuke started in 2013, but never met expectations and didn’t become the Sable replacement it was supposed to be.

The result likely means higher prices for natural gas in the Maritimes in the short term and possibly much longer if calls for renewed onshore gas development, a contentious but potentially lucrative issue for cash-strapped provincial governments, aren’t heeded.

“We do believe the closures of Deep Panuke and Sable will result in higher gas prices in the Maritimes,” said Steve Moran, chief executive of Corridor Resources Inc., a junior oil and gas company based in Halifax, which stands to benefit now that the biggest local sources of gas are gone.

Corridor produces natural gas in the McCully Field near Sussex in southern New Brunswick, though only during the winter when prices are strong. It is now eyeing further development in the province’s Frederick Brook Shale, a hydrocarbon-rich layer up to 1,100 metres thick.

“That’s the prize. Our main focus in 2019 will be trying to secure a joint-venture partner for the Frederick Brook Shale,” Moran said. “Certainly, high natural gas prices enhance the potential for future expansion in New Brunswick.”

Corridor’s expansion ambitions are also being aided by the New Brunswick Progressive Conservative government’s warm approach to hydraulic fracturing, which fractures layers of shale to release pockets of gas by pumping water and chemicals under pressure deep underground.

Premier Blaine Higgs, a former Irving Oil Ltd. executive, has moved to renew natural gas development in the province, although the government said a province-wide fracking moratorium remains in place.

“The provincial government has given all indications that they’re interested in new investment in the oil and gas sector in New Brunswick and are actively speaking with potential investors and potential proponents and developers,” said Colleen Mitchell, president of the Atlantica Centre for Energy, an industry group.

Corridor has not determined when it might frack again in New Brunswick. But Mitchell predicts new gas development will arrive in New Brunswick in 2020.

A domestic supply from onshore sources would help shield consumers from rising prices, she said, in part by avoiding pipeline tolls that must be paid to import gas through the 1,101-kilometre Maritimes and Northeast Pipeline, which connects Nova Scotia and Massachusetts.

“There is a significant threat to natural gas users with the traditional supply of natural gas ending,” Mitchell said, referring to Nova Scotia’s offshore supply.

Nova Scotia and New Brunswick are not as well connected to North American gas markets

Nova Scotia and New Brunswick natural gas customers already pay the highest average residential gas bills in Canada, according to the National Energy Board.

Bills in those provinces average nearly $160 a month, roughly double the averages in British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan, where consumers can access large amounts of low-cost gas through well-developed pipeline systems. Nova Scotia and New Brunswick are not as well connected to North American gas markets.

“Our prices here are higher,” said John Hawkins, president of Heritage Gas Ltd., the only natural gas utility in Nova Scotia.

Heritage, owned by Calgary-based AltaGas Canada Inc., supplies residential, commercial and industrial customers, and the vast majority of its supply used to arrive from offshore sources.

Hawkins said prices for Heritage customers will increase in the near term, but will eventually stabilize thanks to two long-term transportation contracts that will bring in gas from hubs in Ontario and the U.S.

We have billions of dollars potentially of onshore natural gas reserves, but nothing can move ahead until there’s some movement (on the moratoriums)

Patrick Brannon, of the Atlantic Provinces Economic Council

Heritage is also planning to store gas — bought at lower prices during the spring and summer — in a large storage facility, which Hawkins expects to be online by 2022.

Storing relatively cheap gas for winter use will cut Heritage customers’ gas costs by 15 to 20 per cent, he said. To further lower costs, he’d like to see domestic onshore gas development.

“We think it would be very helpful to have that happen here in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick,” Hawkins said.

Patrick Brannon, director of major projects at the Atlantic Provinces Economic Council, said onshore natural gas development holds “tremendous” though currently unlocked potential.

“We have billions of dollars potentially of onshore natural gas reserves, but nothing can move ahead until there’s some movement (on the moratoriums),” he said, referring to fracking bans in Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. “It’s definitely an opportunity for Nova Scotia and New Brunswick. Doing nothing isn’t really an option.”

Offshore development is also quiet, with no exploration underway in Nova Scotia, although the provincial government said the future of offshore exploration “remains positive.”

In a statement, the Department of Energy and Mines said it regularly has discussions with “major global” companies.

“There’s a tremendous amount of oil and gas out there — eight billion barrels of oil and 120 trillion cubic feet of gas,” the department said. “This is a long-term process, and we need to be patient. When the time and market conditions are right, there will be more activity.”

The Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board, a provincial regulator, issued a new call for exploration bids in December for an area around Sable Island, a national park.

In response, more than 3,300 letters of concern have been written to federal and provincial politicians that call for the bidding round to be cancelled, according to the Halifax-based Ecology Action Centre.

“Seismic blasting for exploration, and the chance of a blow-out or spill near Sable Island National Park Reserve pose undue risks to the entire ecosystem,” said Stephen Thomas, the centre’s energy campaign coordinator.

The centre is among a number of parties calling for a moratorium on both offshore oil and gas drilling in Nova Scotia and a public inquiry into the Canada-Nova Scotia Offshore Petroleum Board.

There are also environmental concerns about the proposed construction of a liquefied natural gas (LNG) terminal in Goldboro, N.S., which could offset the loss of offshore production jobs in the province.

Thomas said the terminal would be Nova Scotia’s single-largest source of greenhouse-gas emissions.

“It’s so energy intensive to liquefy natural gas,” he said. “I don’t see how we could ever move forward with building that plant and meet any climate targets in the future.”

But Brannon, at the Atlantic Provinces Economic Council, notes the $10-billion project would bring 3,500 construction jobs over four years, though the project’s proponent — Calgary-based Pieridae Energy Ltd. — has not made a final investment decision. If constructed, the terminal would be used to export North American LNG to Europe by sea.

You can read more of the news on source