One year ago, Vancouver-based Ballard Power Systems’ Inc.’s stock was on fire.

The hydrogen fuel cell stack designer and manufacturer has been around since 1979 despite the fact there still isn’t a market of any scale for its products.

The stars seemed to align as 2020 ended and 2021 dawned: optimism swelled around the prospect that U.S. President Biden would sweep into office and pour money into creating a hydrogen economy — which seemed to mirror what the Chinese government had in mind, when last September it set a new target to put one million fuel cell vehicles on its roads by 2030.

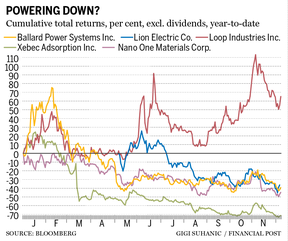

But a year is a long time, and though Ballard’s stock surged 157 per cent, rising from $20.93 per share in September 2020 to $53.90 by February 2021, it has now tumbled to $17.02.

If the investment bubble around Ballard has burst, it’s certainly not the only company in Canada’s cleantech sector that witnessed huge gains in their share price early in 2021, only to see them come crashing down.

Many analysts say it’s a natural hangover from 2020 — a year in which governments in Europe, the U.S., China, and Canada signalled plans for major emission reduction stimulus programs. But some have been slow to materialize, and some programs have been scrapped, leaving investors focused on the companies’ long road to executing their ambitious plans.

I think realism sort of re-entered this space

Kate Charlton

“I think realism sort of re-entered this space,” said Kate Charlton, vice president of investor relations at Ballard. “Like, OK, let’s start looking at the fundamentals, let’s start looking at the growth trajectory, so I think there was a level setting across the sector.”

Indeed, the reasons may vary, but taken as a group, the sheen around Canada’s cleantech sector disappeared in the last three quarters of the year.

Lion Electric Co., a Montreal-based electric bus and truck manufacturer that has won praise, and hundreds of millions of dollars in federal and provincial money to build assembly plants in Quebec, reached $28.39 per share in June. Now, it is trading at $12.57 per share — a 55 per cent drop.

Xebec Adsorption Inc., a Montreal clean energy company that converts methane leakage from landfills and elsewhere into renewable natural gas, peaked at $11.11 per share in January. It has since fallen 78 per cent to $2.45.

Vancouver’s Nano One Materials Corp., which designs lithium-ion battery anodes, peaked at $6.09 per share in January then fell 47 per cent to $3.21.

Loop Energy, which like Ballard designs and manufactures hydrogen fuel cell stacks, debuted on the Toronto Stock Exchange in February, and was trading at $16.90 per share by March but has since dropped to $4.34, or roughly 74 per cent.

What binds the companies together is that each is making a product connected to the transition away from fossil fuels, much of which is being driven by government policies and emission targets.

Rupert Merer, an analyst at National Bank Financial, who covers several of the companies listed above plus others not mentioned, said much of the share price is driven by fund flows. Many Canadian cleantech companies are listed in the major environmental exchange traded funds, which saw enormous support at key moments in late 2020 and early 2021.

“Sector-wide, we saw a huge inflow of capital at the beginning of the year,” said Merer. “We thought it might come back with COP26, and it really hasn’t.”

But cleantech companies listed in U.S. exchanges, from electric vehicle makers such as Tesla Inc. and Rivian Automotive Inc. to Canada’s own battery recycler, Li-Cycle Holdings Corp., continue to see sky-high premiums and trade at massive valuations in relation to their revenues.

“If we put aside the share price performance for a moment, and just look at this valuation on these companies, yes the prices are down but it doesn’t seem like the market is saying these companies aren’t on a path to growth,” said Merer.

The Canadian stocks on a relative basis are actually more attractive, he said, given that investors are assigning lower multiples.

Still, trying to tap an emerging demand for an emerging product is a difficult proposition; and many analysts are trying to figure out whether the market got ahead of the company, or whether the company got ahead of the market.

At Ballard, for example, the company entered 2021 preparing for a groundswell of demand for its hydrogen fuel cell stacks: it expanded its production capacity in British Columbia by six times — at a cost of roughly US$20 million.

Meanwhile, last year, chief executive Randy MacEwen spent his Christmas and New Year’s Eve quarantined alone in a guarded hotel suite in China, where the company is building what he has described as the largest manufacturing facility in the world for heavy duty hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, capable of producing 20,000 vehicles per year, at a cost of around US$67 million.

Together, the expansions cost US$87 million, and the company posted US$96 million in revenue over the trailing 12 months.

MacEwen has said the company is also hoping to reduce the costs of making its fuel cell stack and module products by 70 per cent by 2024. Some analysts say the company’s plan to try cut costs by achieving scale makes sense, but so far the scale it’s preparing for hasn’t materialized.

In China, it struck a joint venture with Weichai Motors, the world’s largest diesel manufacturer, hoping to gain entry into the market. While the Chinese government has started announcing the names of regions where it will fund research into hydrogen technology and start to develop an industry chain, so far it hasn’t added Shandong Province — where Ballard built its plant — to that list.

Charlton, the Ballard spokeswoman, said the company isn’t worried about it, but at the most recent earnings call, MacEwen fielded five questions about China — including when he expects clarity on government policies, whether domestic competitors are catching up technology-wise, when the next sale might come there and so on.

He called the lack of policy clarity out of China “disappointing,” and referred to the market as a “wildcard” for its growth projections, but ultimately couldn’t really predict when the market will pick up. The company has formed many partnerships, including in North America and Europe, all of which MacEwen said could soon translate into revenue.

“I think the question is when will we see what’s the linkage between when the order book starts to materialize and then subsequently revenue,” said MacEwen. “I think it’s — a year is about right.”

Whether it’s out of freefall yet isn’t clear — the stock dropped 13 per cent in November following its earnings calls, as analysts ramped down expectations for revenues.

“There’s been sort of a shift in focus from what space are you exposed to, to can you execute on the growth in this space,” said Sean Keaney, an analyst with Eight Capital Research. “I think that Ballard as a cleantech bellwether has maybe been a lightning rod for that kind of attention.”

Investors are starting to realize that while government policies are clearly driving an energy transition, it’s going to take awhile, said Keaney.

In the meantime, investors seem focused on execution: supply chain issues have been headline news for months, and Merer said Lion Electric encountered problems obtaining enough adhesive materials to build its products, and thus its “works in progress” inventory has been slowly building.

At Xebec, the company continues to make its clean energy systems at a profit, but it had to revise its guidance after it missed revenue expectations.

Some companies, such as Ballard simply don’t issue guidance. It’s been through a bubble in 2000 — the original dot-com bubble — when it’s share price surpassed $164 and then plummeted to less than a dollar and rarely broke above $5 in the ensuing two decades.

Somehow, it survived.

“Ballard has been around for longer than I have been alive,” said Charlton.

Financial Post

• Email: [email protected] | Twitter: GabeFriedz

_____________________________________________________________

If you liked this story, sign up for more in the FP Energy newsletter.

______________________________________________________________

You can read more of the news on source