Over the weekend, exposed oil fields and processing facilities in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia were bombed by drones. Suddenly, almost 6 million barrels-a-day of the world’s oil supply was taken offline.

We haven’t seen this scale of disruption in 40 years, not since the Arab Oil Embargo and the Iran-Iraq war.

What can we learn from four decades ago?

Answer: A lot about energy transitions and how difficult it really is to ‘get off oil.’

Déjà vu For Some of Us

We don’t know how long the present outage will last, whether it will happen again, or of greater concern whether the tension will escalate into a regional military conflict involving Iran.

Speaking of Iran, today’s Saudi oil supply disruption is déjà vu for those who remember. The last time we saw over five million barrels-a-day taken offline was in 1979. Back then the Iranian Revolution was quickly followed by the gruesome Iran-Iraq war. From an energy viewpoint, that conflict took 7 million barrels-a-day off the global market, pushing nominal oil prices up from US$15 to a high of US$38/barrel (See Figure 1).

In fact, the price shock of ’79 was the second in a decade. Half-a-dozen years prior, in 1973, Arab countries had united to vent their anger at the Western world. Unhappy with supporters of Israel in the Yom Kippur War, oil-rich countries like Saudi Arabia, Syria, Egypt and Libya turned the valves down on Canada, the United States, several European countries and Japan. Referred to as the Arab Oil Embargo, the united action was tight enough to cause energy havoc around the world.

The price of oil soared and economies receded. Hostage to the geopolitics, each country had to fend for themselves, sourcing scarce supplies. National hoarding of petroleum products took root. Populist anger was easy to stoke; people had to deal with high prices, lineups at the pump, and the discomfort of having their gas-guzzling cars dependent on faraway places they didn’t understand.

In my book, A Thousand Barrels a Second, (McGraw-Hill NY, 2006) I called this type of event a “Break Point”, a confluence of forces that triggers a snap energy transition out of necessity. Two oil price shocks and a feeling of energy insecurity led to an intense period of policy action that materially transitioned the energy supply of every oil-addicted, industrialized economy. During this period, the populist narrative was to ‘get off oil’, and especially off of Middle Eastern dependency.

After the Break Point

Around the world, get-off-oil policies centered on squeezing petroleum out of the electric power generation market. In transportation, the focus was on making vehicles more fuel efficient.

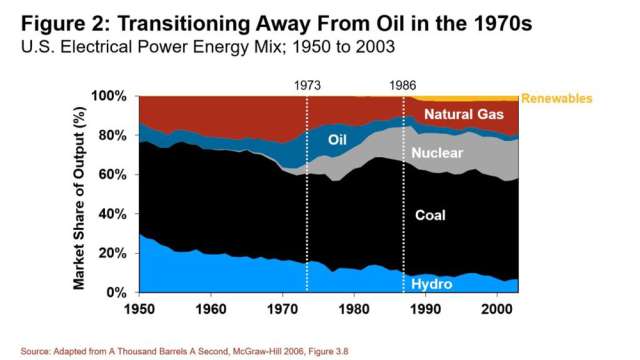

In 1973, 17 per cent of electrical power in the United States was generated by burning oil. The centralized nature of big power plants made them ripe targets for substitution. And there was a new alternative technology ready and waiting: Nuclear power. There was another nascent alternative too: Liquefied natural gas (LNG). And back in the day when climate change was of little concern, the domestic coal industry was only happy to step in and push Middle Eastern oil out of the way (See Figure 2).

President Jimmy Carter’s 1978 Fuel Use Act effectively banned the use of oil in power generation (none of this namby-pamby carbon tax stuff). Around the world, from Japan to Europe, countries legislated draconian action to lessen oil dependency.

In Detroit, automakers were told to make smaller cars and put big-finned gas guzzlers on a diet. Back then the average car logged 12.5 miles per gallon. Corporate Average Fuel Efficiency (CAFE) standards were introduced, targeting 27.5 mpg by 1990. Individual behaviour wasn’t exempted: In the United States, speed limits were reduced to 55 miles per hour (88 km/hr) to save fuel. Around the industrialized world, there was much action in this era of insecurity.

Looking back, the results were convincing. Electric power markets truly transitioned off of oil. Every country did it differently; France went mostly to nukes; Japan championed LNG and the U.S. used a mix of alternatives.

For the first time since oil made its way into the world’s energy arteries in the 1860s, there was true demand contraction as a result of high price, transition and efficiency. In six years, between 1979 and 1985, top line oil consumption fell 8 per cent, from 65 to 60 million barrels-a-day.

Then, in the mid-1980s the price of oil tumbled again. And it was like nothing had happened. Consumption growth, inefficiency and dependency made a comeback.

Today’s Ineffective Narrative

These days the “get off oil” narrative is bellowing out of the climate change megaphone. But environmental concern is not as piercing an issue to the public as a sudden assault on one’s wallet and the fear of having to line up for fuel.

The numbers speak for themselves. After a dozen years of incessant publicity on the perils of climate change, countless policy initiatives around the world, and $4.1 trillion dollars of spending on renewables there is virtually no change in the global energy mix. For every joule of “clean energy” being added to the world’s energy mix at least another joule of fossil energy is added too. That’s not transition; that’s diversification.

Despite the smoke screen headlines we’re being led to believe, there is no reduction in daily oil use. Consumption levels today are over 65 per cent higher than when the world chanted “get off oil” four decades ago. The only realistic debate is how much more we’re going to use next year, not whether or not we’re going to use more.

Lessons for Today

Let’s be honest. Modest carbon taxes, virtue signalling and polarized shouting matches are not going to induce a Break Point that will change the world.

Yes, electric cars are starting to penetrate the market, but even the most aggressive forecasts show that the substitution is going to be painfully slow. Only the most aspirational scenario shows an 8 per cent drop in oil consumption in 6 years (as happened following the 1970s oil price shocks). In reality, the barriers for change today are much higher than in the 1980s when power substitution was relatively easy to achieve.

Nevertheless, here is one of many lessons from the 1970s: A proven way to transition away from some oil use is to start a war, create a shortage that spikes prices; induce energy insecurity; and foment a scapegoat on the other side of the world.

We may be headed there.

You can read more of the news on source