An important hearing kicked off in May before the Canadian Energy Regulator. It’s about the future of the Canadian oil industry. Its subject is the number one threat to Canadian oil production and prices over the next decade — arguably as important as climate change.

I speak, of course, of the Enbridge Inc.’s Mainline firm contracting application.

Toll hearings are the blocking-and-tackling of pipeline infrastructure. Who pays and how much. They are far away from the controversial and well-covered hearings on new pipeline investments. No commissioner ever cried at a toll hearing.

But this one is important. The intervenors opposing Enbridge Inc.’s application — mostly Canadian oil producers — use some of the foulest language I’ve ever seen in a regulatory application, including the dreaded “abuse of market power” accusation.

Enbridge, in contrast, claims this step is required to provide shippers with the long-term priority access they want and reduce the Mainline’s future volume risk.

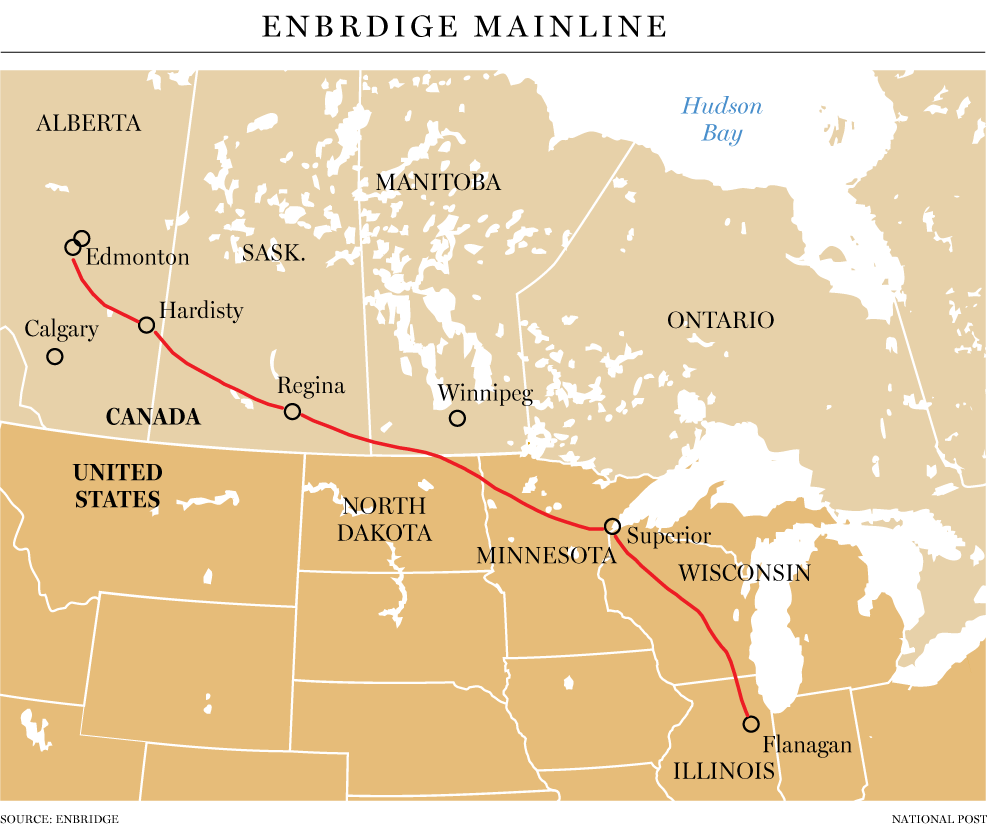

Everybody knows that pipelines are very hard to build. That increases the value of pipelines that already exist. The Enbridge Mainline moves almost three million barrels every day from western Canada to markets in the U.S. Midwest and beyond. It accounts for 70 per cent of all the oil moved from western Canada. It’s an extremely valuable and important asset for Enbridge and all Canadians.

What is the value of a barrel of oil? Without a route to market, the value of the barrel is zero. A large, important pipeline that moves a vast majority of the oil from a transport-constrained basin is therefore, in theory, worth the entire value of oil production from that basin.

Without the Enbridge Mainline, stranded western Canadian oil production would be worthless. Wars have been fought over less.

In order to prevent the owners of pipelines from unfairly profiting from their unique position at a supply chain pinch point, regulation limits not just how pipelines operate but also how much they charge. The CER, in addition to all its other jobs, is charged with ensuring that a pipeline’s fee is just and reasonable.

What a pipeline charges is not left up to the market.

And this is a huge problem for Enbridge. A new pipeline, owned by you and me, the Trans Mountain Expansion (TMX) will soon be in operation. Most forecasters, including Enbridge’s, believe that the pipeline shortage of the last decade will change to a pipeline excess.

When there’s an excess of pipelines, by definition they are not running chock-full of oil anymore. Enbridge’s volume risk here is higher than that of any other pipeline, because not only is it massive, but it’s a “common carrier.”

Pipelines can be tolled two ways. One is analogous to a wedding reception, where the happy couple guarantees a guest count, menu, wine, everything. If the wedding is called off the night before, too bad: it’s all paid for. This is called “firm contract.”

New pipelines are built under firm contracts. They are risky. Without firm contracts, new pipelines would never get built.

Unlike a wedding, a restaurant reservation has no cost and no risk to the client. Pipelines that operate as restaurants are “common carriers.” Enbridge Mainline shippers can make a different shipping decision every month.

For Enbridge, this poses an issue because the new TMX is under firm contract. That pipe will flow at contracted capacity: its shippers are paying for the volume anyway. It means that the common carrier Mainline will disproportionately see volume declines, because there’s no contract committing shippers to the pipe.

In all the ways Enbridge could choose to respond to this threat, they took the most aggressive: attempting to contract the Mainline under firm service. This effectively transfers the risk of declining volumes from Enbridge to the firm shippers. Enbridge accurately states that most shippers want this.

A pipeline with volume declines will see rising costs as economies of scale are lost, and more costs need to be recovered on fewer barrels. This can lead to a death spiral of increasing tolls leading to more volume losses. Everyone — Enbridge, shippers, producers, taxpayers — want to avoid that outcome.

So far this is just business. Enbridge sees a threat to a crown jewel and is responding to shed some of that risk to its customers.

But one important detail makes it a matter of national concern.

Most volumes shipped on the Mainline are under the control of American refiners. Shippers accounting for 70 per cent of Mainline volumes support firm contracting, and only two of these are companies headquartered in Canada and majority owned by Canadians: Cenovus Energy Inc. (which owns refineries in the Midwest) and tiny Vermillion Energy Inc.

Remember, Enbridge cannot sell pipeline capacity to just anyone for any price. It’s bound by regulation. But that same constraint doesn’t extend to shippers who control firm capacity. They can do whatever they want with it. They want this control so badly that they’re willing to sign decade-long deals to get it.

Canadians fought hard to own and control their oil resources. Now, in a low-level regulatory hearing that few even know is happening, we may end up ceding control to foreign entities.

Control of the pipeline means control of our resource. Environmental groups know this. The Canadian producers intervening against Enbridge’s application know this. Our politicians know this.

The toll hearing at the CER, which end on June 25, is instead about who effectively controls Canadian resources, what price they receive, and what the proceeds are used for. It’s a deeply political question left unaddressed by the weird call-and-response format of a regulatory proceeding.

Refiners want low oil prices. Producers and taxpayers want high prices: high prices pay for capital investment and Canada’s enviable standard of living. Placing the Mainline under the control of a small number of refiners wanting low prices materially enhances the bargaining position of those refiners.

This is why Canadian producers are extremely upset. Enbridge’s sensible position is that refiners who want to pay more for the capacity should have it. And if this were a simple matter of business, Enbridge would have a point.

For Enbridge, its toll application is just business. For the rest of us, it’s hugely consequential. Someone should pay attention.

Samir Kayande is an independent business strategy consultant with 25 years of energy expertise.

_____________________________________________________________

If you liked this story sign up for more in the FP Energy Newsletter.

_____________________________________________________________

You can read more of the news on source