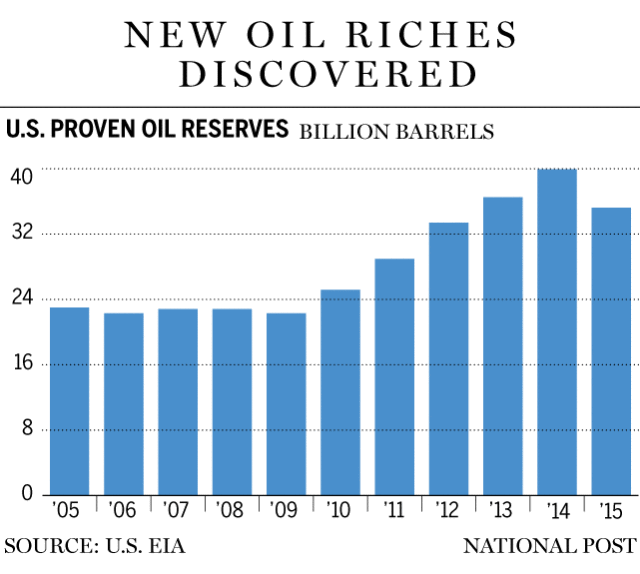

Highly-leveraged financing and cutting-edge technologies have fuelled the discovery of new U.S. reserves in recent years.

The United States’ transformation from an imports-dependent energy consumer to an oil and gas powerhouse in around half a decade is nothing short of breathtaking.

And it’s just getting started.

The implications of this transformation go far beyond global oil markets and are reshaping the global economic order. The three-year oil price downturn starting in 2014 was induced by U.S. shale and has already rocked many nations in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries that have to scramble to find new sources of revenues and appease their citizens. Growing liquefied natural gas exports from the U.S. to Europe can, over time, start diminishing Russia’s dominance in European energy markets.

America’s oil renaissance also has huge implications for Canadian oil producers and the wider economy, which has manifested itself in many direct and indirect ways. Canadian producers have already seen investment dollars move out of the oilpatch and into the U.S. Some Alberta producers and oil driller are also channeling more investments into the U.S. rather than back home.

Meanwhile, American oil and natural gas have already reached the shores of China and other Asian markets, even as Canadian governments and companies weigh the pros and cons of selling fossil fuels to the world’s fastest-growing, energy-hungry markets.

Here’s the U.S.’s short but epic journey from a grateful importer of OPEC oil to a promising global energy exporter.

It all began when hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling techniques were combined to unlock the riches buried deep within American soil. Out came shale oil and gas and discoveries that have turned shale basins of North Dakota, Texas and other American states into the Silicon Valleys of oil, where highly-leveraged financing and cutting-edge technologies have fuelled the discovery of new reserves in recent years.

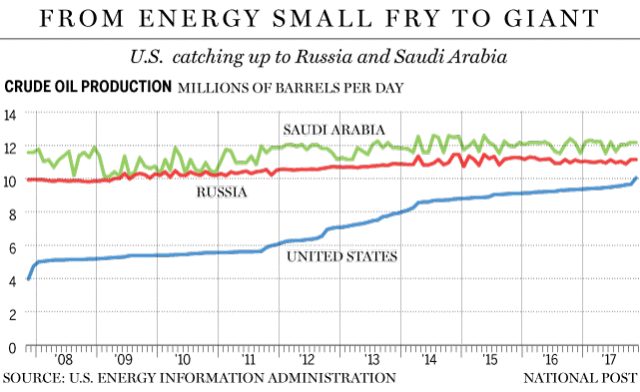

In November, the U.S. crossed the magic 10 million barrels per day mark for the first time in more than 48 years, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration’s latest report published Jan. 31. It had crossed that figure twice — in October and November of 1970, but after that it had embarked on terminal decline until shale oil came along over the past decade to revive its oil fortunes.

“BOOM!,” exclaimed an RBC Capital Markets report Thursday, awed by the rapid pace of U.S. production. “The torrid pace of production growth of almost 850,000 bpd since late summer underscores the anti-fragile nature of production in a rising price environment despite a stagnant rig count,” RBC analysts said.

Indeed, the U.S. producers’ resilience threaten to disrupt OPEC and Russian machinations to control global oil markets.

Most analysts believe the three countries are not expected to raise production much more from these very elevated levels. So expect the U.S. to remain a very big thorn in the sides of Saudi Arabia and Russia for quite some time.

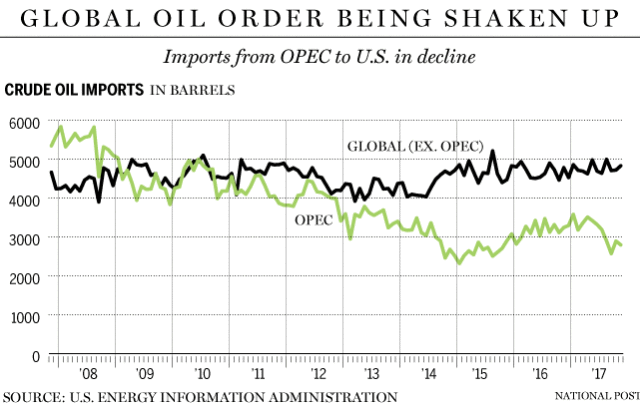

Surging domestic production means American dependence on global oil imports has diminished greatly. OPEC countries have suffered the most as their light blends are being displaced by U.S. shale.

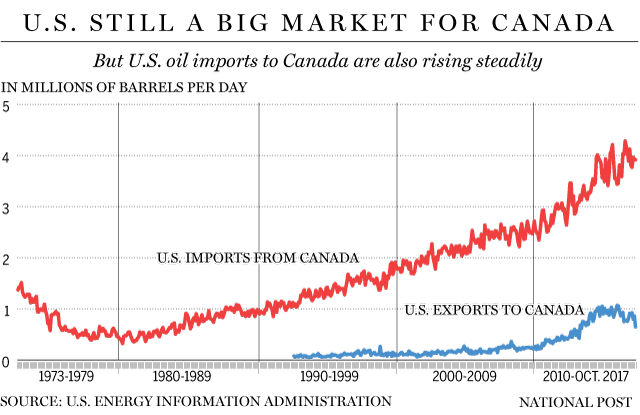

Rising American production has, luckily, not displaced Canadian oil exports to U.S. — for now. In fact, Canadian oil exports have surged as U.S. refineries especially on the Gulf Coast prefer heavier Canadian oil over light shale. But it’s no a longer a one-way street: American oil exports to Eastern Canada have galloped ahead in recent years, mostly at the expense of oil from OPEC countries.

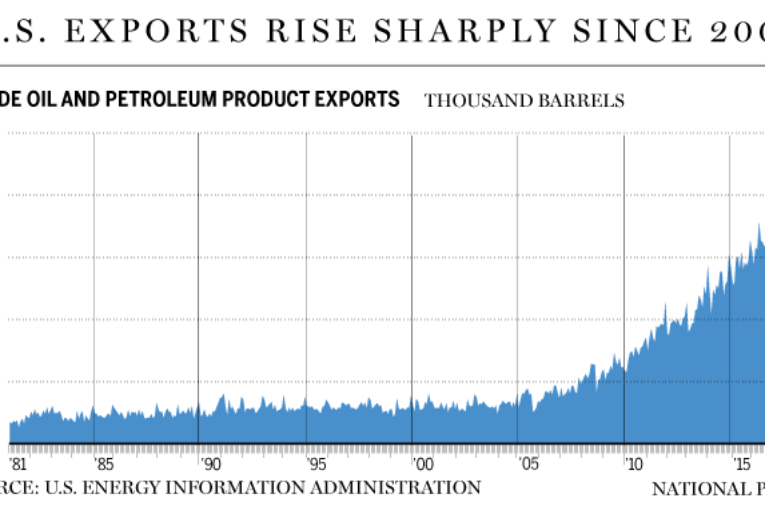

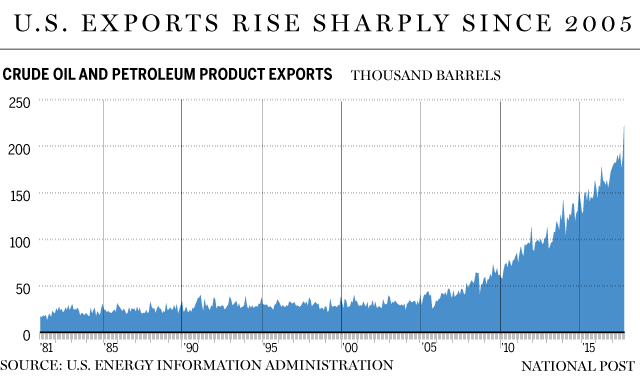

Probably the most important chart of all: while the U.S. remains a small oil exporter, its shipments have picked up considerably after the U.S. Congress lifted a 40-year ban on oil exports in late 2015. Previously, U.S. could only import to Canada.

So much so that Canada, once the only regular buyer of U.S. crude, finds itself competing with refiners in Europe and Asia. Last April, China bought more than Canada did for the first time, according to Bloomberg.

This is the chart that Saudi Arabia and Russia — and even Canada — should fear the most, as the U.S. is emerging as a vital ‘swing exporter’. If the U.S. starts exporting many more barrels of black gold to places like Europe and Asia it would grab market share from Russia and Saudi Arabia. Canada, which is already losing investment dollars to the U.S., would also see its ambition to build West Coast export pipelines falter if U.S. shale starts meeting Asian demand.

Graphics by Gigi Suhanic

• Email:

You can read more of the news on source