It’s a whole new ballgame for climate action and clean growth in Canada. The climate deal struck late Friday in Ottawa committed premiers and the prime minister to work together to hit our country’s emission targets. Despite two holdouts — Manitoba and Saskatchewan — that’s an unprecedented accomplishment on climate change in our federation.

Thanks largely to B.C. Premier Christy Clark’s brinkmanship and Saskatchewan Premier Brad Wall’s continued opposition, one part of the new agreement — putting a price on carbon pollution — dominated Friday’s discussions.

Despite some tense moments, the approach to carbon pricing that Prime Minister Trudeau announced back in October remains essentially intact. The “concession” B.C. won — a commitment to an interim review of the carbon pricing policy in 2020, instead of the full 2022 review Ottawa had planned — is a small change, and one that could actually help strengthen the national approach.

So although there’s guaranteed to be some squabbling in the backseat (and maybe even some wrong turns), our governments have finally packed the essentials and hit the road.

Carbon pricing is a fantastic climate policy — but it accounts for just two pages of the nearly fifty in the body of the new framework. So with the drama of negotiations behind us, here are a couple other parts of Friday’s agreement that matter for climate and clean energy.

Are we there yet?

From a climate point of view, the key expectation of Friday’s meeting was that it would deliver enough emission reductions to hit Canada’s 2030 target.

The document doesn’t have a lot of numbers in it, but governments did publish some new analysis of how far we’ve come and how much further we have to travel.

Here’s what it means:

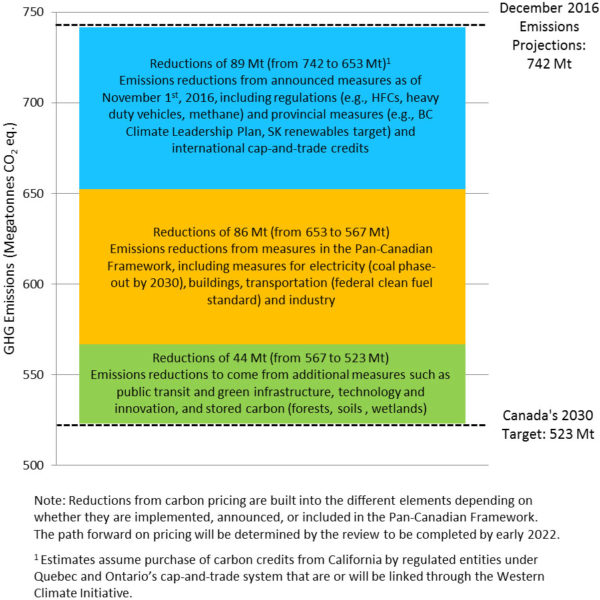

- The top of this chart — 742 million tonnes — is the level that Ottawa projects Canada’s emissions would reach in 2030 without new measures to cut them.

- The blue portion shows the cuts to carbon pollution we can expect from policies that governments across Canada have adopted up to November 2016.

- The yellow section shows the contribution of Friday’s framework. That’s mainly the reductions from a series of climate policy announcements Ottawa made in the run-up to the First Ministers’ meeting.

- And the green segment shows the reductions we still need to find to hit Canada’s 2030 target, a total of 44 million tonnes.

The chart lists some areas that could deliver that final tranche of cuts to carbon pollution: planting trees, public transit investments, and so on. It doesn’t mention another option that could deliver a big chunk of those reductions — namely, continuing to increase the carbon price after 2022 — but the framework does hint at doing so, stating that a carbon pricing review will “confirm the path forward, including continued increases in stringency.”

No doubt about it: there’s still a lot more work ahead of us. The policies governments have already promised have yet to be implemented effectively, and the “potential” emission cuts in the green section of the chart still need to be nailed down.

So although there’s guaranteed to be some squabbling in the backseat (and maybe even some wrong turns), our governments have finally packed the essentials and hit the road.

Building on the best

We witnessed the messy side of setting climate policies cooperatively on Friday: Saskatchewan refused to play ball, B.C. called an audible, and Manitoba wanted to move to a whole other stadium.

But the new plan also includes some commitments that illustrate the upside of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s national approach, which allows provinces to pioneer policy and then have Ottawa help scale it up to a Canada-wide standard.

Take reducing emissions from buildings. Earlier this year, Ontario committed to implementing a stronger building code by 2030, one that will require new buildings to be “net-zero carbon emissions.” (Net-zero buildings are so efficient that they could be powered solely through clean power generated onsite.)

That was a leading commitment when Ontario made it — but as of Friday, it’s on the way to becoming a national one. Federal, provincial and territorial governments set a goal of developing and adopting the same standard on the same timeline. The national framework even went a step further, pledging a new code to make buildings more efficient whenever they’re renovated.

Earlier in the fall, we commissioned economic modelling to look at the benefits of building on the best elements of today’s provincial climate policies. For a net-zero building code specifically, we found the cuts to carbon pollution would grow by 121 per cent if Ontario’s approach became the national standard.

Another of today’s provincial best practices is Quebec’s Zero Emission Vehicle mandate, which requires a growing number of vehicles sold in the province to be emissions-free. Friday’s result didn’t get us all the way there, but it did commit to a “Canada-wide strategy for zero-emission vehicles” by 2018, along with a promise of more charging infrastructure for electric cars.

In sector after sector, governments have now given themselves the tools they need to hit the target, but they still need to use them properly to craft these policies. So it’s important that the framework also promises monitoring, public reporting, increasing ambition, expert analysis and advice, and reporting back to first ministers each year.

Climate policy is never easy, and neither is managing the relationships between the governments in our federation. But as of last week, Canada is on the field and looking for a win.

This article was originally published on iPolitics.

You can read more of the news on source