For months, investors have been wondering how Toronto-based Barrick Gold Corp. would add to its future new project pipeline after it sat out a round of industry consolidation over the past couple of years.

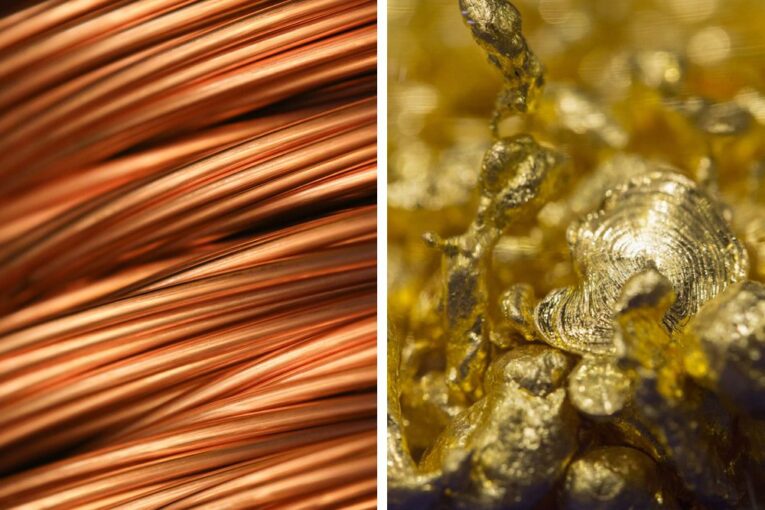

Barrick partly answered that question on March 20, announcing a deal, in principle, with Pakistan’s government to restart work on Reko Diq, one of the world’s largest undeveloped copper and gold deposits.

Reko Diq, which many investors and analysts forgot about after a contentious legal dispute halted the project in 2011, would require billions of dollars of investment to build and take many years to complete. But it could potentially give Barrick a shot in the arm: past studies indicated the site contains billions of pounds of copper and millions of ounces of gold, and could produce for multiple decades.

“It’s still really early, so it’s hard for us to say what this all looks like,” said Jackie Przybylowski, an analyst at BMO Capital Markets, who covers Barrick. “But I think it’s just an example of how mining companies are having to move more into different jurisdictions, and less obvious ones, or less common ones.”

After more than a decade of scouring the United States, Canada, Latin America and Australia, many mining companies are increasingly looking in countries and jurisdictions that are less connected to the Western economies.

Barrick has long had a diversified geographic portfolio; it now has projects in various states of development in Japan, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, Papua New Guinea and Pakistan.

Przybylowski also noted that increasingly, the largest gold miners are looking at copper. This is in part because copper demand is expected to grow as a result of increased electrification and the energy transition, but also because geologically, recent discoveries have shown that copper often occurs alongside gold in large scale deposits.

A 2010 feasibility study of Reko Diq estimated the site could contain as much 54 billion pounds of copper and 42 million ounces of gold. In its 2010 annual report, Barrick said it envisioned building a mine in Pakistan that would produce 100,000 ounces of gold and between 150 to 160 million pounds of copper on average each year over the first five years. A lot has changed since then, and Barrick said it would need to update its projections based on current market conditions.

Barrick, which has long derived its profits from gold, is increasingly looking at copper.

“Copper’s contribution to the bottom line is increasing,” chief executive Mark Bristow said repeatedly during the company’s fourth-quarter earnings call on Feb. 16.

“We have every intention of growing our business, both in copper and in gold — or in gold and then in copper,” said Bristow. “And the principle behind Barrick’s business philosophy is high-quality assets. That’s our focus. And so that’s what we’re hunting, whether it’s gold or copper.”

But he also said the company has invested to embed copper expertise in its exploration teams because the copper business had not always been so profitable in the past.

Bristow was not available to discuss his agreement with Pakistan on Reko Diq.

Under the framework agreement Barrick announced on March 20, the company would operate the mine and own 50 per cent of the project. The other 50 per cent would be divided between the government of the province of Balochistan and various state-owned enterprises. Barrick’s original partner, Antofagasta PLC, will be replaced in the project by the Pakistani parties.

Josh Wolfson, an analyst at RBC Capital Markets, wrote that the project could add at least two per cent to Barrick’s net asset value — based on the payout to Antofogasta, which was paid a reported US$900 million for its 37.5 per cent stake in the project.

The revival of Reko Diq marks a sharp reversal for a project that had been dropped from most of Barrick’s investor presentations years ago, only to resurface in 2019 when the World Bank’s International Centre for the Settlement of Investment Disputes ordered the Islamic Republic of Pakistan to pay US$5.83 billion to a Barrick Gold Corp. joint venture subsidiary for blocking the mining project.

The award included US$4.087 billion in damages, which the arbitrators calculated was the fair value of the Reko Diq project at the time of the arbitration and US$1.75 billion in ongoing interest, plus US$62 million in legal costs.

To put that into perspective, Pakistan’s military budget in 2020 was US$10.3 billion, according to the World Bank.

For that reason, many analysts doubted that Barrick would receive such a lump sum cash payment from Pakistan.

Others have criticized the investment-state arbitration forums that produce such awards, such as Gus Van Harten, a professor and associate dean at Osgoode Hall Law School, who said it tends to favour investors over states such as Pakistan.

“The difficulty with this award, and with all investment treaty arbitration awards since the arbitrations exploded about 20 years ago, is they emerge from a process which lacks institutional safeguards of judicial independence and procedural fairness,” Van Harten told the Financial Post in 2019. “As a result, in my view none of the outcomes have the credibility of a judicial decision.”

One filing from the legal dispute around Reko Diq showed that lawyers for Pakistan had claimed that no project of the size and scale of Reko Diq had ever been built in Balochistan, and that the mining exploration permit was never a guarantee a mining lease would be granted.

Nonetheless, Barrick appears to be moving toward a definitive agreement to restart development work on the mine.

• Email: [email protected] | Twitter: GabeFriedz

You can read more of the news on source