In the last days of December, Australia’s Wyloo Metals Ltd. offered $617 million in cash to buy Noront Resources Ltd., ending a bidding war with fellow Australian mining giant BHP Group, and emerging as the presumptive new owner of the collection of mineral claims in Ontario’s James Bay Lowlands known as the Ring of Fire.

The deal, expected to close in the next few months, leads to at least one major question: What happens next in the Ring of Fire?

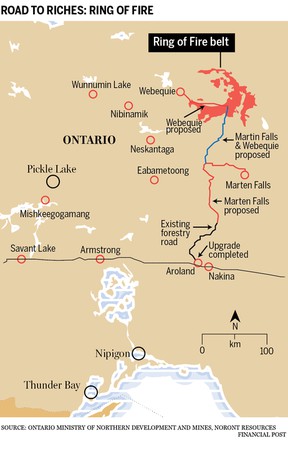

Cut off from the rest of Ontario, the project would require more than $1 billion of taxpayer investment in roads and infrastructure.

Against this backdrop, Wyloo Metals head Luca Giacovazzi has said that the Ring of Fire is one of the most prospective mineral belts in the world and that he’s laser-focused on building a nickel mine there, within the next five years, which could help feed raw materials for an electric vehicle battery supply chain in Canada.

It’s almost like you’re handed the perfect deposit

Luca Giacovazzi

“It’s almost like you’re handed the perfect deposit,” Giacovazzi told the Financial Post, from his home in Perth. “The best way to think of it is, in our neck of the woods, in western Australia, [this] would have been mined out ten years ago. It would have started mining ten years ago and it would have been at the end of its mine life by now — that’s how high quality the ore body is.”

But it has not been mined yet, in part because of its location. The Ring of Fire, as it is now known, is located in what has been described as the second largest peatlands complex in the world, storing an estimated 35 billion tonnes of carbon; and it is situated in a broader region that is inhabited by roughly a dozen First Nations communities, some of which have expressed reservations about the impacts of a large scale-mining project in what remains a pristine area.

Those factors mean that before any mine can be built, a series of roads must be constructed, which requires a half-dozen federal and provincial environmental assessments. But the total impact of opening the area to development remains unclear until Wyloo takes control, and offers more clear guidance on which mines and mineral deposits it intends to develop.

For now, Wyloo has said it is heavily focused on nickel, which is expected to see increased demand, and is already surging in price, as countries around the world call on automakers to offer and sell more electric vehicles. Nickel can make up more than half of the metal in a battery.

In Canada, in order to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, the federal Liberal government has mandated that 100 per cent of all new vehicles sold must be zero-emission vehicles by 2035, which means primarily electric vehicles. EVs currently make up about three to four per cent of new vehicle sales, and there will need to be a step change in sales to meet the government’s interim targets of 10 per cent by 2025, and 50 per cent by 2030.

But amidst the growing political debate about net-zero emissions, and calls for new supply chains in Canada, the proposal to open the James Bay Lowlands to mining has renewed the debate about reconciliation with Indigenous peoples.

In November, Neskantaga First Nation filed a court application in the Ontario Superior Court of Justice in Toronto, claiming that it faces multiple crises, including a boil-water advisory and the pandemic, and that it has not been adequately consulted by Ontario provincial officials working on an environmental assessment on a road, which would run through its territory, as part of the Ring of Fire project.

The application cites Neskantaga’s rights under a number of laws, including Treaty Number 9 — which established hunting, fishing and other rights in the Lowlands area — and was signed more than a century ago.

“Neskantaga First Nation files this Application following years of raising concerns over the potential impacts on its homelands, including: environmental harm to land and water; negative impacts to species relied upon as part of Neskantaga’s culture and way of life; harvesting and fishing rights; and to longstanding Treaty rights owed to Neskantaga under Treaty No. 9, as well as unextinguished Aboriginal rights and title dating since time immemorial,” the court application states.

Similarly, Kate Kempton, a lawyer for Attawapiskat, has raised concerns about the federal government’s draft framework for a regional assessment, which sets the scope of the environmental impact assessment, and is open for comments until early next year.

The First Nations should be leading the environmental review process, given they are the only people who live in the region, she said.

Kempton said that with the pandemic raging, Attawapiskat is not in a position to gather information, and hire experts to help understand the impacts of a large-scale mining project.

Plus, she said the process has been split up, with different environmental assessments for different components of the road, and separate federal and provincial layers, making it difficult to follow.

“It’s a confusing convoluted mess,” she said, “and it makes it difficult for under-resourced First Nations communities to keep up.”

But two First Nations’ communities, Marten Falls and Webequie, are leading provincial-level environmental assessments that look at the impacts of roads that would link their communities to a north-south road leading to the Ring of Fire.

It’s a confusing convoluted mess and it makes it difficult for under-resourced First Nations communities to keep up

Kate Kempton

Meanwhile, federal officials are also still moving forward on an environmental review, including a regional assessment of the Ring of Fire area that would take a comprehensive look at the environment and its vulnerabilities.

They have set a Feb. 1 deadline for anyone to comment on the terms of reference, essentially a framework, for the proposed regional assessment. But there is pushback. The East Coast Environmental Law Association sent a letter Dec. 20 to the federal Impact Assessment Agency asking for an extension. Meanwhile, several First Nations, including Neskantaga, Attawapiskat, and Fort Albany wrote in November to Environment Minister Steven Guilbeault calling for a meeting and alerting him that they declared “a moratorium” on development in the area, asserting authority under various laws and treaties.

In the letter, obtained by the Financial Post, chiefs from all three First Nations object to the environmental review process, saying it offers them only “tokenistic involvement.”

“We and our neighbouring First Nations in northern Ontario have been the only human inhabitants of the muskeg since time immemorial,” the letter states.

Karen Fish, communications manager for the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, said her agency has taken the circumstances arising from COVID-19 under consideration, which is why it paused its process for several months in 2020.

“There will be many opportunities for Indigenous communities to continue to be involved in the Regional Assessment process,” Fish said by email, saying they are holding virtual information sessions and collecting feedback.

Joanna Sivasankaran, a spokesperson for Natural Resources Canada, said her agency has not committed any fiscal support to any part of the Ring of Fire, and that she could not say much about the project because the environmental review processes were underway and not complete.

Giacovazzi declined to comment on the objections from First Nations’ communities, saying he had not yet had a chance to speak with them.

While a conflict brews over who has authority over development in the remote patch of land, there is the other question about how exactly Wyloo would look to develop the collection of mineral claims once it takes ownership.

Giacovazzi said his company wants to develop the Eagle’s Nest deposit first, which contains nickel, copper, platinum and palladium. Under Noront’s plan, that deposit would have an anticipated mine life of 11 years, plus potential for nine additional years, but Giacovazzi has said his company would look to update the plan with input from its team of engineers and geologists.

“This won’t be a 10-year mining operation,” he said.

Noront also controls at least four chromite deposits — a metal used in the production of stainless steel. Giacovazzi said the deposits could support mines for five or six decades, but equivocated on when exactly his company would look to develop them.

“It’s not a burgeoning market like nickel is,” he said. “They require a bit more work, and a bigger investment to get them off the ground. You want to make sure you get it right, and you want to make sure the market conditions are right.”

All of these uncertainties have added complexity to the idea that the Ring of Fire could be quickly, easily or cheaply opened to mining. That uncertainty has existed for years, but it’s taken on new urgency as Wyloo brings new capital to the projects.

While the federal and provincial governments have started the environmental review process for building a 450-kilometre, all-season road and upgrading a 97-kilometre stretch of road to connect the area with the rest of Ontario, there has been little public debate about the cost.

According to a document from a 2019 meeting between Noront and the deputy minister of Infrastructure Canada, Noront had estimated it would cost $1.1 billion to $1.6 billion to construct and was asking for a federal contribution of $557 to $779 million.

“An all-season road would primarily benefit mining companies, who would not contribute financially,” the 2019 note to the deputy minister, obtained by the Financial Post, states.

Similarly, Wyloo’s Giacovazzi has said the government should pay for the road.

“We’re not under any kind of illusion that it’s going to take one year,” he said. “We know it’s a process.”

Financial Post

• Email: [email protected] | Twitter: GabeFriedz

You can read more of the news on source