At the end of the climate conference in Glasgow, Scotland, Alok Sharma, president of the United Nations’ 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26), fought tears as he announced that 197 countries had only been able to agree to “phasing down” the use of coal, rather than “phasing out” one of the main sources of global warming.

“May I say to all delegates I apologize for the way this process has unfolded and I am deeply sorry,” Sharma, a minister in British Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s cabinet, said at the culmination of the two-week summit on Nov. 13.

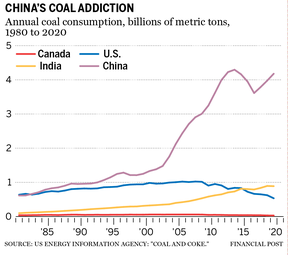

China and India, each a big polluter with populations that exceed one billion people, refused at the last minute to commit to quitting coal. Sharma’s failure to secure a consensus to end coal’s reign wouldn’t have surprised anyone watching commodity markets. The pandemic has stirred up multiple economic forces that undermine the prevailing narrative that the dirtiest fuel source is on its way out.

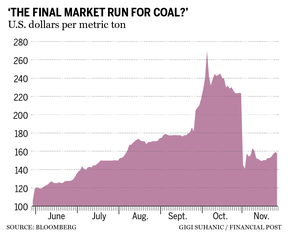

“Is this the final market run for coal? I would say probably not,” Andrew Blumenfeld, who analyzes North American coal markets at IHS Markit, said in an interview.

Commodity markets show coal remains very much in demand. In October, the price of coal for delivery in northwest Europe surged by more than 300 per cent to US$231, compared with prices that were hovering around US$50 before the pandemic, according to McCloskey price assessments provided by IHS Markit. In southern China, prices spiked to US$251 from about US$80 in February 2020.

Few saw such a dramatic swing coming.

Is this the final market run for coal? I would say probably not

Andrew Blumenfeld, analyst, IHS Markit

Until about a decade ago, thermal coal had been one of the predominant energy sources mined and burned to produce electricity and heat. In 2010, it made up nearly 45 per cent of the energy mix in the United States, compared with 25 per cent for natural gas, about 20 per cent for nuclear, eight per cent for hydro, and three per cent for wind, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA).

EIA data for China and India is less comprehensive, but fossil fuels made up 80 per cent of their energy mix a decade ago, and most of that would have been coal, Blumenfeld said.

But as governments began taking climate change more seriously, and technological advances lowered the cost of cleaner energy sources, the overriding narrative was that greener politicians or market forces were well on their way to putting coal out of business.

For example, Ontario eliminated all coal-fired electricity in 2014 , primarily replacing the source of a quarter of its power with hydro and nuclear. Recent policy initiatives by the current Alberta government set the province on a course to close all coal power plants by 2023 — accelerating an earlier timeline of 2061 — and Nova Scotia, which relies on coal for more than 60 per cent of its electricity, is set to cut off coal by 2030, according to the Pembina Institute and Canada Energy Regulator .

In the U.S., natural gas became more economical than thermal coal beginning around 2008, Blumenfeld said. Stricter environmental regulations raised the costs associated with coal, giving natural gas an additional edge.

Natural gas took over coal’s place as the dominant fuel source by 2020, accounting for about 40 per cent of total energy, compared with 20 per cent for coal. (Wind climbed to 8.5 per cent, while solar entered the picture and represented about three per cent of the energy mix.)

Even in China and India, where worsening air quality over the past decade has created major health and political issues, authorities appeared keen to end their dependence on coal.

Fossil fuels now make up about 66 per cent and 76 per cent of their energy mix, respectively. Renewables are growing, if slowly. Solar makes up four per cent of the supply for both countries, while wind makes up six per cent in China and five per cent in India.

However, government rhetoric about the urgency of a green transition hasn’t translated into enough investment in renewables to make coal redundant, at least not yet.

Storage capacity technology isn’t advanced enough to make wind and solar a reliable energy source, ensuring that coal remains part of the mix, even in countries with solid green reputations such as Germany, Blumenfeld said.

Further stoking the demand for coal was an especially cold winter last year in parts of the Northern Hemisphere, and unusually hot summers in the past couple of years, said Edward Gardner, a commodities economist at Capital Economics.

The global recovery from the COVID-19 crisis put even more pressure on energy supplies. China led the rebound, and because it remains a big user of coal, demand surged beyond existing supply. Miners hadn’t invested in new production because all indications were that demand was fading.

Extreme flooding in China, combined with stricter rules governing mine safety, added to supply constraints by hobbling the country’s domestic sources, forcing the country to enter international markets. Indonesia, another big coal producer, also suffered floods that forced mines to close, squeezing global stockpiles.

These factors — the weather, dwindling investment and a surprisingly strong recovery — created “the perfect storm” for prices and production to jump, Gardner said. And because these factors still persist, it suggests the market surge has exposed a gap between coal and renewables that could make kicking coal difficult.

“The last thing any country wants is to be short of electric power, especially in winter,” Blumenfeld said.

The last thing any country wants is to be short of electric power, especially in winter source

Andrew Blumenfeld

Natural gas prices also spiked this year due to a mismatch between demand and supply, forcing many countries to return to coal as a replacement for the cleaner fuel. But the U.S. and Russia have indicated they will increase supplies of natural gas, which could reduce demand for coal. Indeed, coal prices in northwestern Europe have plunged by 35 per cent from their October peak, and prices in southern China dropped 17 per cent.

Still, coal prices remain elevated compared to last winter. In the midst of power outages last month, China commanded its domestic producers to boost coal production and placed a cap on their prices in order to encourage utility companies to keep electricity flowing.

Though China promised to end financing of new coal power plants abroad at the UN General Assembly in September, it didn’t make immediate commitments that would curb domestic usage. It even still has domestic coal power plant projects in the pipeline, said Ilaria Mazzocco, fellow with the Trustee Chair in Chinese Business and Economics at the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

At COP26, climate watchers had hoped Chinese President Xi Jinping would set a firm date when he reiterated the country’s pledge to reduce carbon emissions by 2030, but they were disappointed. The earliest China observers can expect a date on peaking emissions is 2026, when the government is set to release its next Five Year Plan on the direction of the economy.

“The Chinese leadership does seem very committed to decarbonization, but they’re also committed to doing it on China’s timeline,” Mazzocco said.

In the U.S., there isn’t a carbon emissions limit. Instead, federal agencies are slowly tackling the coal industry. The Environmental Protection Agency last month delivered a deadline to comply with new rules that would require generators to retrofit their facilities to clean their wastewater of toxic heavy metals by 2025. However, there’s a provision to allow power plants to remain online without retrofits, prolonging operations, until they are forced to shut down in 2028 for non-compliance.

Evidence of a quicker pulse in the coal industry might even rekindle investor interest, which could result in increased production, at least on the margins.

Tyler Mordy, chief executive at Forstrong Global Asset Management Inc. in Toronto, has exposure to coal through mixed-energy exchange-traded funds. He recognizes that coal is “a left-for-dead asset class,” but sees opportunity in fossil fuels overall.

The pandemic helped make Mordy’s bet on coal a profitable one. Another unpredictable crisis, such as further waves of COVID-19 infections or more natural disasters, could force countries back into old, dirty habits.

“As long as coal production remains a big component of power generation and the ability to find a dispatchable source of electricity, I think the possibility of this happening in the future remains,” Blumenfeld said.

Financial Post

• Email: [email protected] | Twitter: biancabharti

_____________________________________________________________

If you liked this story, sign up for more in the FP Economy newsletter.

______________________________________________________________

You can read more of the news on source