Rio Tinto Plc.’s latest investment in a Quebec aluminum smelter is another example of how Canada’s natural resources will remain an investment magnet in the new, more sustainable economy.

Earlier this month, the metal giant announced a $110-million investment its aluminum smelters in Quebec — believed to be the first investment of any scale in any new North American aluminum production following about a decade of stasis, during which China’s sector rose to dominance.

Rio’s investment remains modest — increasing the company’s aluminum production by less than one per cent — but the global mining giant is touting Quebec’s clean hydroelectric energy, and the low-emission process that it uses to smelt as a primary driver behind the expansion.

“We’ve got hydropower, and we’ve got the lowest carbon aluminum smelting technology in the world,” Ivan Vella, chief executive of aluminum at Rio Tinto, told the Financial Post. “You put those pieces together and we think that’s something we should invest in.”

That rationale is likely to take on new life in policy discussions of how Canada can best meet its goal of reducing emissions 40 to 45 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030 without damaging, and indeed, still growing the economy.

Already, the federal government has set aside $8 billion in a Strategic Innovation Fund to help decarbonize industries and has started doling out hundreds of millions of dollars to help steel, cement and other sectors cut emissions.

When you think about the energy transition, building more coal plants … is not a very attractive proposition

Ivan Vella

But among analysts and industry executives, the debate about whether so-called green industrial products could fetch a premium any time soon, is far from settled. Meanwhile, some climate change advocates question whether green industry actually creates net benefits for the environment.

Rio said it is using AP60 technology that emits less than 2 tonnes of greenhouse gases for every tonne of aluminum produced compared to an industry average of between 10 to 14 tonnes of emissions. The investment will add 16 new smelting cells at its AP60 plant in the Saguenay-Lac-Saint-Jean region of Quebec.

Separately, since 2018, Rio and Alcoa Corp. have been developing a process to produce carbon-free aluminum through their Elysis LP joint venture. Embraced by Apple Inc., beverage makers and others, and supported by the Quebec and federal government, Rio is currently developing the process through prototype cells at its Alma smelter, located in the same region of Quebec, but the technology won’t be ready until 2024, and won’t be producing large volumes until two years after that.

Vella, the Rio executive, framed the $110 million investment in Quebec, which will come into production in 2023, as a bet against coal, which has traditionally been used to smelt aluminum.

He predicted aluminum demand would grow 3.3 per cent per year in the next few years, based on use in construction, but also from electric vehicles, solar panels, and other applications.

“The supply side is going to be more challenged,” said Vella. “When you think about the energy transition, building more coal plants … is not a very attractive proposition. It’s not to say a country may not do that, but you know it’s difficult.”

The investment comes at a time when aluminum prices are suddenly surging, which most analysts say is only tangentially related to the energy transition, and has much more to do with Chinese industrial policy and new constraints on that country’s production.

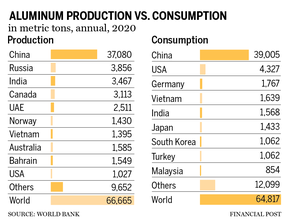

According to the World Bank , China produced 55.6 per cent of global aluminum in 2020. Russia, India, Canada and the United Arab Emirates are next in line, each producing between 3.7 and 5.8 per cent of global supply.

“For the past 20 years, we woke up every day, and the Chinese were adding (aluminum) capacity,” said Gregory Wittbecker, a U.S.-based senior analyst of the aluminum market with CRU Group, a commodity research firm. “We basically haven’t added any capacity outside of China in that time.”

But Wittbecker said a new policy in China is capping primary production. That was partly driven by decarbonization efforts: Chinese industrial planners constructed several large hydroelectric dams to help the industry pivot away from coal, but severe droughts exacerbated energy shortages and forced the country to divert energy away from industrial sectors, like aluminum smelters, to regular consumers, he said.

The other main issue is China is running into trade barriers that limit its exports into key markets, including the U.S. and Europe, Wittbecker said.

Those two factors have affected aluminum prices more than anything, he said.

Although there are numerous aluminum prices, based on the region and type, he picked the London Metal Exchange price of around US$2,700 per tonne as a standard-bearer, and said it’s questionable whether a “green” or less carbon-intensive product — whether from Quebec, Norway, Iceland, the Middle East or somewhere else — can fetch a premium.

“The premiums are pretty modest,” said Wittbecker, “They range from US$5 to US$20 per tonne.”

But increasingly, producing low-carbon aluminum is necessary to sell your product at market prices because buyers insist on it, he said.

Jean Simard, president and chief executive of the Aluminum Association of Canada, cited the same shifts in Chinese industrial policy as the main factors that have lifted aluminum prices.

But he said that the market for less-carbon intensive commodities, whether aluminum or steel, is still in its infancy. Producers may prefer small premiums for a period of time, he said.

“Let’s say an (Apple) iPad cost 1,000 bucks, and you have two dollars worth of aluminum,” Simard said, “The impact (of adding less-carbon intensive aluminum) on the consumer is not prohibitive, but the added value for the brand is worth it.”

Many economists believe that the market for green industrial products is still emerging and the policies that could accelerate it have yet to take hold.

Alan Krupnick, an economist and senior fellow at Washington, D.C.-based Resources for the Future, said it’s still not clear how much “greening” the industry actually helps the environment.

For example, he questioned whether the additional hydroelectricity that Rio will use to increase its smelter output could force another customer to use a fossil fuel energy, thereby transferring emissions to a different user.

Simon Letendre, a Rio spokesman said the company owns six electric dams in Quebec and has agreements with Hydro-Quebec for its power, but did not answer questions about whether it has sold excess electricity in the past.

Krupnick, who studies green procurement policies and carbon border tax adjustments, said that investors and rating agencies are putting pressure on industrial companies to track and reduce their emissions but as yet the government policies that could create actual “markets” for less-carbon intensive products — with posted premium prices, standardized benchmarks of what constitutes ‘green’ and auditing — have not been fleshed out.

There are signs that the process is underway and markets are developing, but it could take years to reach a mature stage, he said.

“In the absence of government regulations that create these markets,” said Krupnick, “it’s hard to see how they’ll be created on their own.”

• Email: [email protected] | Twitter: GabeFriedz

_____________________________________________________________

If you like this story sign up for FP Energy Newsletter.

_____________________________________________________________

You can read more of the news on source