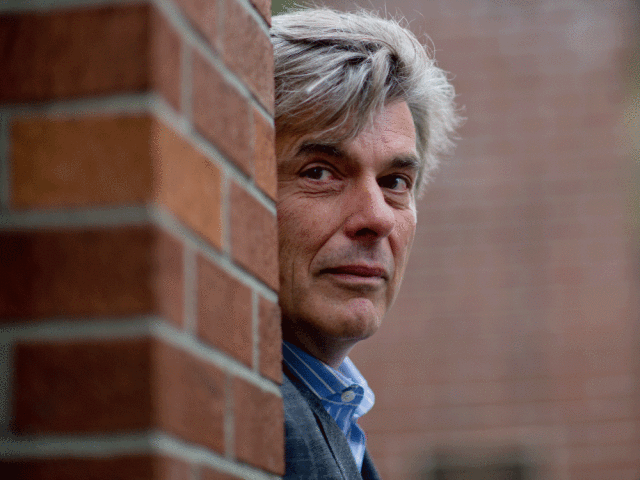

Dan Wicklum, one of the oilsands’ most influential scientists, believes Alberta’s oilsands sector will decades from now look back on the construction of a facility this year in southeast Calgary to convert greenhouse gas emissions from a gas-powered power plant into valuable products as the next big chapter in its evolution.

The facility at the Shepard Energy Centre is a big deal, because it has the potential to solve the industry’s emissions challenges, as well as create a whole new industry to export GHG reduction technology to address climate change, said Wicklum, chief executive of Canada’s Oil Sands Innovation Alliance (COSIA), a five-year-old consortium of eight companies that are pooling resources and technologies to accelerate and share advancements.

“Canada, Alberta, is at the forefront of this sector” to capture and utilize carbon, Wicklum said. “This (oilsands) sector is not looking inward. That is the sign of a dying sector. What companies are doing through COSIA is looking around the world for technologies, new partners, new ways of thinking, new ways of communicating challenges.”

Rather than shrinking due to pressures from governments to reduce environmental impacts and from fossil fuel critics pushing greener energy sources, Wicklum believes the oilsands can be a hub for finding solutions to the world’s biggest environmental challenges.

In addition to the GHG conversion facility, COSIA is working on a pipeline of innovations — covering things such as decreasing emissions from oilsands production, treating water, and reducing land disturbance and tailings — that is so rich the sector’s long-term future is “remarkably optimistic,” he said.

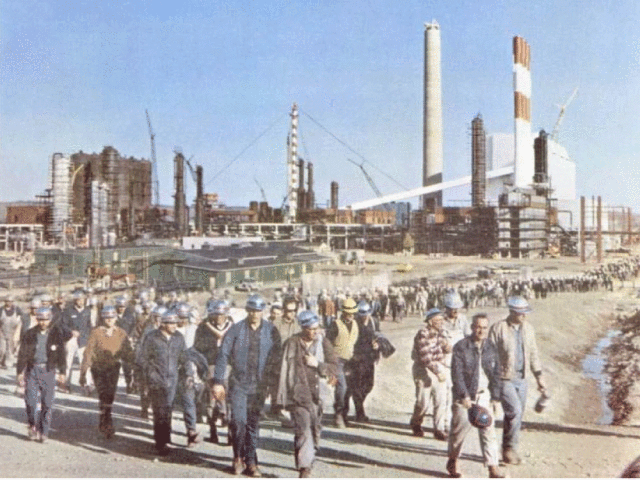

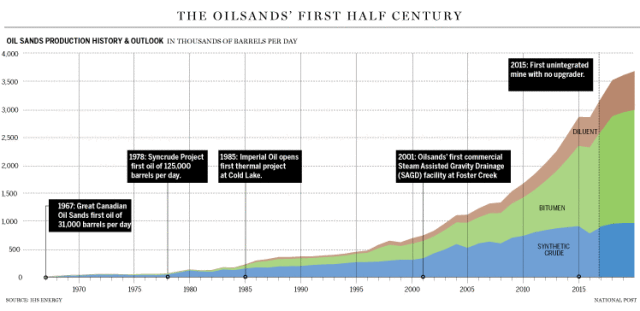

Wicklum is hardly alone in his upbeat view of the oilsands. Fifty years after Great Canadian Oil Sands — predecessor of oilsands powerhouse Suncor Energy Inc. — first began producing oil on Sept. 30, 1967, there’s renewed optimism that the next 50 years will bring more growth and prosperity for Alberta and for Canada.

Despite continuing policy and market setbacks, and the belief that the oilsands’ age, much like that of coal, has expired in a carbon-constrained world, some even see a future measured in centuries.

This (oilsands) sector is not looking inward. What companies are doing is looking around the world for technologies, new partners, new ways of thinking, new ways of communicating challenges

Dan Wicklum, COSIA

In an interview just before he died of leukemia in August, Rick George, who as Suncor’s chief executive did more than anyone to turn the sector into an economic powerhouse, predicted: “We will be producing oilsands for another 300 to 500 years.”

Such a long horizon is unusual in today’s world, where technologies come and go in months.

Yet from the very beginning, the oilsands inspired visions that looked out decades because the size of the treasure — the world’s third-largest oil deposit in a relatively stable place — requires large-scale projects and massive investment to build them. That drive to solve challenges is usually unappreciated by those outside the industry.

It’s with that long game in mind that COSIA — comprised of Suncor, Canadian Natural Resources Ltd., CNOOC Nexen Ltd., Cenovus Energy Inc., ConocoPhillips, Devon Energy Corp., Imperial Oil Ltd., and Royal Dutch Shell PLC — is building the GHG conversion facility as part of an international competition: the US$20-million NRG COSIA Carbon XPRIZE.

Finalists will soon get to test their ideas to transform CO2 collected from the 860-megawatt Shepard Energy Centre, owned by Enmax Energy Corp. and Capital Power, into products ranging from fish food to building materials.

The Alberta and federal government pledged in March a combined $20 million in funding to support the facility, one of the world’s few where carbon-conversion technologies will be tested on a commercial scale.

Any successes will help the long-term picture, but conditions are grimmer in the short term. The most recent oil shock pushed industry players to consolidate, cut costs and in some cases leave the business altogether.

Wicklum said COSIA’s budget remains the same despite having lost some of its founding members. Established operators such as Suncor and Canadian Natural have purchased the operations of those that exited and are even more motivated to improve because oilsands is their core business, he said.

Still, tensions continue between those who see the potential and the need, and those who see risks and better options. The upside is that the sector is forced to continuously improve to prove its naysayers wrong and remain in business. The downside is that its existence is constantly in question and under threat.

Oil Change International is one of many environmental NGOs that believe the oilsands’ days are — and must be — numbered.

In a June 2017 report, the Washington, D.C.-based group said oilsands growth was a historical anomaly that resulted from unusually high oil prices between 2010 and 2014. But weaker future oil prices, political and public opposition to infrastructure such as pipelines, and increased regulatory stringency have eroded the economic and political climate that promised inevitable growth, the group said, with the flight of international oil majors sending a signal that there will be no recovery.

In addition, “Canada is currently grappling with meeting its Paris climate goals,” the group said. “Recognizing that there is no new growth planned for the sector provides an important political incentive to plan for the sector’s inevitable decline in line with safe climate limits. A diversification plan is critical to minimize risks for workers, communities and governments, while maximizing benefits of the transition.”

Jeff Rubin, a former CIBC economist and one-time oil booster, now sees oilsands’ growth as incompatible with Canada’s commitments to reduce greenhouse gases and a decline in oil consumption resulting from the rapid adoption of electric vehicles.

He argues there is no need for Canada to build new pipelines to export bitumen to Asia, because prices there would be lower, not higher, than those obtained in its unique and only North American market.

“Instead of benefiting from another three decades of business-as-usual growth, where world oil demand can reliably be counted on to grow at least one per cent a year, oilsands producers can expect to be operating in a sharply contracting global market that would shut down as much as half of today’s nearly 97 million bpd of production,” Rubin writes in a paper for the Centre for International Governance Innovation.

He goes on to say that the new climate mitigation reality poses a “lethal” outlook for the future of the oilsands, and much of Canada’s pipeline capacity will become redundant “in the face of what can only be a massive contraction in oilsands production over the next three decades.”

Oilsands producers can expectu2028 to be operating in a sharply contracting global market that would shut down as much as halfu2028 of the nearly 97 million bpd of production

Jeff Rubin, former CIBC economist and one-time oil booster

Such negative views, usually held by oilsands outsiders, are so pervasive they are influencing Canadian energy policy.

Eager to show environmental leadership, politicians have introduced a barrage of controls, such as a 100-megatonne-a-year cap on oilsands emissions that is expected to run out of space within a decade, carbon taxes and measures to hinder construction of oilsands pipelines.

The policy impediments far outweigh weak oil prices as the oilsands’ major future risk, said Ken Green, senior director of the Center for Natural Resource Studies at the Fraser Institute.

“The oilsands face significant challenge, but they are mostly governmental in making,” he said. “I don’t think they are there for lack of a market and I don’t think they are for lack of ingenuity or technology that can service that market. The problem is that the ingenuity and determination are based on the expectation of profit, and the various layers of regulation and government activity have struck much of that profitability away.”

Green believes current governments are pushing the industry into a slow wind down by hyper-regulating pipelines, inflating rail transport costs through tougher rail car standards, adding carbon taxes, setting up a tanker ban, obstructing port access, and putting in tougher sulphur rules and an emissions cap.

The sector is losing momentum, resulting in skilled labour migrating to other places and a diminished profile, which, in turn, will make it harder to re-start growth, he said.

Yet many top energy forecasters and industry experts don’t share the gloom, since a growing global population will increase the demand for oil alongside other energy sources.

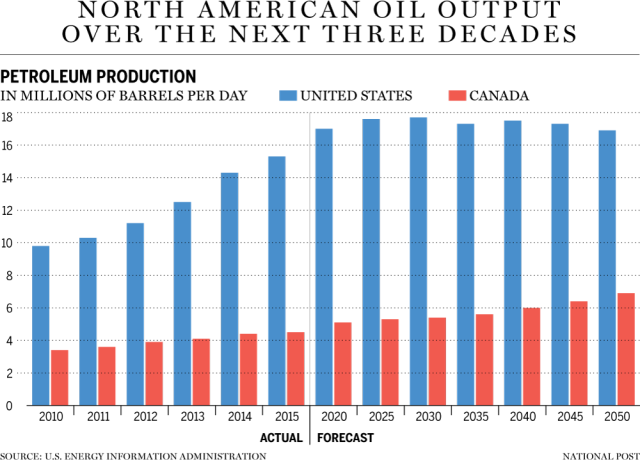

The U.S. Energy Information Administration in its Sept. 14 International Energy Outlook 2017 predicted Canadian oil production would rise by 1.26 million barrels a day by 2040, mostly from the oilsands.

The National Energy Board sees Canadian crude oil production increasing from 4 million b/d in 2015 to 5.7 million b/d in 2040, a 41-per-cent increase, driven primarily by a 72-per-cent increase in oilsands production, which would reach 4.3 million b/d by 2040, up from 2.5 million b/d in its reference or middle-of-the-road scenario.

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, which gets input directly from its member companies, has oilsands production rising to 3.7 million b/d by 2030, up 1.3 million b/d from 2016 levels, though way short of the 6 million b/d of approved production capacity.

Over that period, the oilsands will be the main contributor to Canada’s overall oil production growth to 5.12 million b/d by 2030, from 3.85 million b/d in 2016, CAPP said.

But after two years of deep and rapid cost cuts to match low oil prices, the next stage of growth will come in smaller and faster increments to compete with sources such as shale oil that can more quickly respond to price signals, said Scott Sharabura, an associate partner in McKinsey & Co.’s Calgary office who advises senior oilsands executives on operational transformation.

This growth phase will be more disciplined and more focused on efficiencies and boosting internal expertise as ways to increase margins, he said.

“It would be hard to see a boom similar to the one we had over the previous 10 years, but a return to growth? I absolutely can see that,” Sharabura said.

Even another oil shock won’t hold the oilsands back, said Gil Dawson, managing partner of Turnstone Strategy Inc., an oil and gas price-forecasting firm in Calgary.

Another shock that could push down prices below US$30 a barrel isn’t out of the question, Dawson said, given that the demand for oil has slowed as the global economy has weakened since 2011 and oil inventories continue to be stubbornly high.

A shock would destabilize producers in the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries that are still reeling from the last one, and it could hammer U.S. tight oil producers that are enjoying an influx of capital, but Dawson said it would not be as hard on oilsands companies that have made themselves more efficient and less leveraged.

The oilsands have already made Canada the fifth-largest oil producer in the world, recently overtaking China, said Kevin Birn, executive director, North American crude oil markets, at global energy consultancy IHS Markit.

The oilsands have also made Canada the world’s largest supplier of heavy sour crude, responsible for more than a third of the global market.

IHS Markit expects the oilsands could expand by nearly 1 million b/d by 2026, adding to the more than 2.6 million b/d produced in 2016. It also expects Canadian heavy oil supply to increase its market share as declines in Mexican heavy production are unlikely to be reversed anytime soon and Venezuelan supply continues to look uncertain.

Birn also said the threat to the industry posed by the growth of electric vehicles has been overstated.

The auto industry sells 90 million cars a year, 98 per cent of them with internal combustion engines, and there is an existing fleet of more than one billion passenger cars around the world with a life expectancy of 15 years, making it unlikely electric vehicles will suddenly push oil out of business, he said.

It could certainly happen “that some cataclysmic shift is going to upend that system — we are not just talking about the oil market, we are talking about the automotive industry as well,” Birn said, “but the inertia, the weight and scale of that system is going to be with us for a while, even in a very aggressive penetration of alternative power.”

Instead, Birn believes the oilsands will continue to stand out as a growing and reliable global supplier of energy because of its “inexhaustible resource potential,” the establishment of a large production base in the past 15 years and significant production cost reductions.

He also points out that global underinvestment during the oil downturn will lead to declines in other regions, increasing geopolitical instability, and that there is a tight market for heavy oil amid a light-oil glut.

Although production growth will be more modest in a lower price environment, “We don’t see a future without growth in the oilsands,” Birn said. “We find it even more remote that there will be less oilsands than there is today, because of that long launching base that now exists in the industry.”

Financial Post

You can read more of the news on source