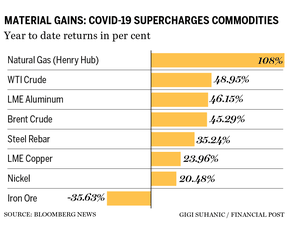

For months, economists have debated why the price of so many commodities — from aluminum, iron ore and copper to natural gas and lumber — have been so volatile: Are these the first signs of structural shifts in supply chains related to the energy transition, or just temporary blips?

There’s consensus on a few points: The pandemic, by halting and then restarting supply chains, threw supply and demand fundamentals out of whack, and pushed many commodity prices up.

A shift in consumer spending away from services, like air travel and dining out, towards durable goods like exercise machines and home renovations, also increased demand for metals and wood products, that contributed to further price increases.

It ties into a larger discussion about whether recent inflation — which Statistics Canada clocked at 4.1 per cent in August, the highest level since 2003 — is transitory or likely to endure for a longer period. When it comes to commodity prices, a half-dozen economists and analysts interviewed for this article described many of the recent price jumps as temporary shocks caused by the pandemic. But in some cases, they said the pandemic may be helping mask structural shifts in commodity markets connected to the energy transition, or could in the future.

“We see this rise in prices, and then you say how much of this rise is whiplash (from the pandemic), and how much is structural?” said Jumana Saleheen, chief economist and head of sustainability at research firm CRU Group. “It’s quite tricky to do and it varies by commodity.”

In May, for example, the price of iron ore reached what CRU analyst Erik Hedborg characterized as a historic high of US$240 per tonne, although it has since been dropping back, falling 22 per cent in the past week alone down to roughly US$100 per tonne.

Hedborg said the rise actually began in 2019 after Vale SA’s Brumadinho dam in Brazil collapsed, tragically killing 270 people.

That tragedy took an iron ore mine out of production and set up a supply crunch. Then, after the pandemic hit, in 2020, China began a massive stimulus to rejuvenate its economy that included large infrastructure investment, and boosted demand for steel, which contains iron ore.

Meanwhile, spending in North America and Europe shifted away from services to durable goods which also propelled prices.

With iron ore, China has since implemented environmental controls that have cut back its steel production, which took some demand off. Hedborg noted iron ore remains substantially elevated from its pre-pandemic range of between US$50 and US$60 per tonne.

Although similar supply-demand dynamics shook other commodities, more complicated factors also took hold.

Saleheen said aluminum prices, which this month hit US$3,000 per tonne for the first time since 2008, were also affected by structural shifts related to the energy transition.

“We’re starting to see that China is becoming more serious about environmental policy and so that’s lead us to revise our view of future supply,” Saleheen said.

Some of that shift has been overshadowed by a military coup earlier this month in Guinea, home to the world’s largest reserves of bauxite — the rock that is processed into alumina, a white powder that is converted into aluminum. That sent jitters through the market but did not result in meaningful impacts, according to CRU analyst Gregory Wittbecker.

Instead, Wittbecker described a “fundamental shift” in China to use more recycled metals in their aluminum production as a means to reduce emissions. That’s simultaneously given rise to the view that its production has plateaued after more than a decade of growth, which is juicing prices, he said.

He’s watching whether aluminum prices rise enough to incentivize the construction of new smelter facilities in Canada.

“The pipeline of projects outside of China is pretty thin,” said Wittbecker. “There’s nothing in Canada or the U.S. that is etched in stone.”

But the structural shifts in the aluminum market may be an anomaly.

John Mothersole, pricing and purchasing research director at research firm IHS Markit, said that the energy transition is likely to result in fundamental shifts for many metals and supply chains, but in most cases those changes remain years away.

“The standout example in my mind is copper,” said Mothersole.

It is a metal found in the batteries that power electric vehicles, and also is prized for its conductivity — a key attribute expected to drive demand as electrification increases.

In May, copper prices touched an all-time high on the London Metals Exchange of US$10,747.50 per tonne. But Mothersole said the impacts to demand from the energy transition won’t have a meaningful affect on supply and demand dynamics until at least 2024.

“When we look at the near-term, we still a market that’s capable of achieving a surplus,” he said, adding, “If our forecast is correct, the market is going to transition for a period into surplus.”

IHS maintains a Materials Price Index, which collects pricing data on a broad basket of items including major metals, oil, lumber, semiconductors, rubber, oceangoing shipping vessels and more.

In May, the index was up 132 per cent year over year, reflecting broad prices increases. It has since declined 12 per cent.

IHS forecasts an additional 23 per cent decline until the end of 2022, but that would still leave the index 31 per cent higher than it was pre-pandemic in 2019, he said.

Mothersole used the term “whiplash” to describe the supply side destruction caused when mines, oil wells or factories shut down connected to pandemic-related labour shortages, delays in investment and other hiccups in the supply chain; and the simultaneous unexpected demand for “durable goods.”

IHS analysts are betting that the mismatch is not permanent and the supply and demand will come back into balance as the pandemic recedes.

“Everyone can agree the post-pandemic world will look a little different than the pre-pandemic world,” said Frank Hoffman, an IHS consultant. “But we’re not going to see this elevated level of demand for durable goods forever.”

“Eventually, people are going to be able to take vacations, shift some of their spending to services,” Hoffman added.

Lumber prices, which Hoffman studies, have already experienced incredible highs and lows: Near the start of the pandemic, many mills shut down affecting supply just as the sudden critical mass of people working from home decided they wanted to make renovations and drove up demand.

But in that market, supply has already overtaken demand. In August, Vancouver’s Canfor Corp., the second largest lumber producer in North America, cut its production in British Columbia — where 55 per cent of its production occurs — by 20 per cent “until demand and pricing meaningfully improve.”

It said lumber prices have declined below “cash costs,” in what BMO analyst Mark Wilde described in one note as “an unprecedented U-turn in lumber markets.”

In May, the price for a thousand board feet of eastern spruce/pine/fir hit an all-time above $2,000 but by Sept. 10 dropped to $630, according to Natural Resources Canada.

“It is a wild time,” said Rory Johnston, a managing director and market economist at Price Street and founder of the newsletter Commodity Context. “Every single commodity feels like it is posting all-time highs or super volatile crashes.”

Johnston said even the “sleepy” natural gas market, where higher prices have always been kept in check by the flexible production of U.S. shale producers has experienced volatility and uncertainty in recent months.

In some ways it’s the usual story of the pandemic upsetting supply and demand dynamics, he said.

Every single commodity feels like it is posting all-time highs or super volatile crashes

Rory Johnston, managing director, market economist, Price Street

But before the pandemic, the energy transition had dimmed investor sentiment around natural gas, and a lack of upstream investment exacerbated the supply and demand mismatch. Then, unusually hot summers in many parts of the world lead to greater energy use and further tightened markets.

Thus, in North America, prices rose from a range of US$3 to US$3.50 per thousand cubic feet before the pandemic to above US$5.

In Europe, Johnston said supply side destruction is taking longer to recover, causing even more pronounced prices.

Not all economists are convinced the supply chain disruptions and distortions caused by the pandemic will persist until the price elevations caused by energy transition structural shifts in markets take hold.

Marc Desormeaux, senior economist at Scotiabank, said that so far, the strength of the global economic recovery has surprised everyone. But new COVID-19 variants have created uncertainty about the length and timing of the pandemic.

“I guess what I would say is prices should remain well-supported for most commodities relative to history,” said Desormeaux, “… but perhaps not as strong we’ve seen this year, and into the back end of last year.”

Financial Post

• Email: [email protected] | Twitter: GabeFriedz

_____________________________________________________________

If you liked this story, sign up for more in the FP Energy newsletter.

_____________________________________________________________

You can read more of the news on source