CALGARY — A packed house erupted into applause as Fred Kerr walked on stage during a warm, mid-August evening at Yuk Yuk’s Comedy Club in Calgary. He was the first featured comic, liquor was flowing and everyone was eager for a good time.

“Folks, like a lot of Calgarians, I lost my job,” the former oilpatch worker said, reaping his first, tentative laugh. “Yeah, I appreciate the sympathy,” Kerr continued. More laughs.

“But I won’t be unemployed for long because I have a bachelor of arts degree.” More laughs. “In French Literature.” More Laughs. “From the University of Calgary.” More laughs.

“You laugh, but the real reason I have confidence in my prospects is because a BA in literature is exactly Justin Trudeau’s qualification.” Big laughs.

He then covered the newsiest topics in his five-minute skit — Donald Trump, marijuana legalization, North Korea — kept the language clean and the political criticism mild to avoid misfiring with the young audience.

Encouraged by a final round of applause, Kerr glided away from the spotlight, satisfied with a good night’s unpaid work.

In reality, Kerr, 54, isn’t optimistic about his job prospects in oil and gas. He was vice-president of investor relations at Pengrowth Energy Corp. when he was laid off in mid-2014 as oil prices started to collapse. Despite having a top-drawer résumé, he remains out of work.

More than 100,000 oilpatch employees — roughly one in three — lost their jobs during the oil downturn of the past three years, according to estimates by the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers (CAPP) and the Canadian Society of Unconventional Resources (CSUR).

Energy prices are recovering, but many are still out of a job, gave up looking for work, retired early or are starting over in entry-level positions in other industries at a fraction of their previous salaries.

Meanwhile, green and other new economy jobs promised by governments as part of their push to transition toward renewable energy have been slow to materialize, and they usually go to better-qualified candidates from other industries when they do.

Government efforts to re-integrate displaced oil workers have been slow and minimal next to the legions of jobless made redundant by the new priorities.

Dan Allan, CSUR president, said job cuts have slowed since the early days of the downturn when companies were adjusting their spending to survive, but people are still losing their jobs as international companies pull out of Canada.

During previous downturns, hiring resumed when prices bounced back, but the jobs seem to have gone for good this time, Allan said.

The pullout of major oil companies such as ConocoPhillips Co. and Royal Dutch Shell PLC makes future job prospects even more ominous because big companies historically hire and train new graduates and the next generations of employees.

“Canada is not considered to be the safe and reliable and friendly environment it used to be five, six, seven years ago,” Allan said. “We have lost investment appeal.”

A new survey by Petroleum Labour Market Information (PetroLMI), which conducts research on energy sector labour trends, highlights the gravity of the situation.

The survey, based on 864 responses — employees, laid-off workers, students and others who have given up looking for work — and whose preliminary results were shared with the Financial Post, found 70 per cent were impacted by the downturn in one way or another, and 35 per cent lost their jobs.

Of the respondents, 30 per cent were engineers, almost 14 per cent worked in business and operations management and support (environment, safety, human resources, office administrators, business analysts), nearly 23 per cent worked in technical services and eight per cent worked in trades. The vast majority — 77 per cent — were Albertans.

Canada is not considered to be the safe and reliable and friendly environment it used to be five, six, seven years ago

Dan Allan, president, Canadian Society of Unconventional Resources

Among the 200 unemployed respondents, a staggering 22.5 per cent said they have been out of work for more than two years and 27.5 per cent have been for more than a year.

Of those, 70 per cent said they are looking for work in any industry, while only 25 per cent want to return to oil and gas.

The findings confirm that it’s highly unlikely all the workers impacted by the downturn will be rehired by the oil and gas industry, said PetroLMI vice-president Carol Howes.

“There are growing worries the recent layoffs, perceived lack of growth and stability in the industry, as well as concerns regarding environmental impacts are all coming together to create a perfect storm,” she said. “And that will have an impact on the industry’s ability to attract and retain the best and the brightest.”

Would-be comic Kerr has spent the past three years looking for work, but few jobs are opening in his field as companies downsize, consolidate or leave town, he said. The jobs that did come up usually went to former oil and gas analysts who are switching their highly paid riskier positions in brokerages for corporate jobs offering steadier pays and shorter working hours.

He is still looking, but has learned to live with less money and to appreciate his freedom. In addition to a BA, Kerr has an MBA from Western University in London, Ont., held senior jobs in institutional sales at FirstEnergy Capital Corp. and Acumen Capital Partners, and worked in investor relations at Petro-Canada and Canadian Airlines International Ltd.

During previous downturns, hiring resumed when prices bounced back, but the jobs seem to have gone for good this time

Fred Kerr, former energy executive during his Yuk Yuk’s comedy routine

Kerr took up comedy to fill his ample spare time and rekindle a passion he enjoyed in his youth.

There are some transferable skills between institutional sales and stand-up comedy, he said, not joking at all.

“Those (sales) jobs involve trying to sell an idea to someone and having to be prepared that they might completely reject the idea. All you have is moral suasion. You have to understand what the audience needs and try to provide it,” he said. “In stand-up, you are trying to find things that are funny to you and then bring the audience along and hope that they can be convinced that that is funny, too.”

The reward in the investment industry is money, he said. In comedy, it’s making people laugh — though there can be good money for those who get good at it, which is his plan.

“It’s like a lot of businesses,” Kerr said. “Five per cent of the people make 95 per cent of the money.”

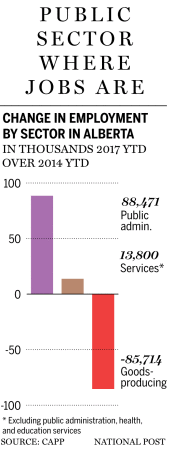

But the lack of employment growth in oil and gas worries groups such as CAPP, said chief executive Tim McMillan. In a recent presentation to the Alberta government calling for a renewed effort to restore investment, his group said policy changes to speed up the transition to renewable energy have had a profound impact on the province’s job market and not in a good way.

Between 40 and 50 regulatory policy and regulatory initiatives underway at the provincial and federal government level are increasing costs and scaring away capital to rival jurisdictions, the group said.

Before the price downturn and before the election of an NDP government in Alberta and a Liberal government in Ottawa, the energy sector employed one out of three Albertans, contributed $10 billion a year in government revenue and 40 per cent of GDP, CAPP said.

The drop in investment means there are 100,000 fewer industry workers in Alberta than there were on average in 2012, 2013 and 2014, it added.

A large number of people are experiencing long-term unemployment, which CAPP said “is associated with permanently lower wages and increased difficulty finding employment, with the potential causes being skill loss and/or the stigmatization of workers who have been unemployed for long periods, making it especially harmful.”

Efforts to encourage upstream oil and gas natural gas investment would help arrest this trend, and also begin to move the province’s job market back into positive territory, the group said.

Efforts to encourage upstream oil and gas natural gas investment would help arrest this trend, and also begin to move the province’s job market back into positive territory, the group said.

The Alberta government has boasted the provincial economy is returning to growth, with a 3.1-per-cent real GDP rise expected in 2017, after a six-per-cent nominal GDP contraction in 2016.

New jobs are being created, nearly 17,000 jobs so far this year, the government said, while unemployment is expected to decline to 7.8 per cent, after reaching a 22-year high last November of nine per cent (Calgary’s unemployment rate was even higher, 10.3 per cent).

CAPP argues most of the hiring has been by government for jobs in health, education and public administration.

Melanie Popp, a 38-year-old single mother with a master’s degree in engineering from the University of Calgary, knows first hand what it’s like to be without a regular paycheque for two years. Her last oil job was at Paramount Resources Ltd., where she specialized in hydraulic fracturing.

To make ends meet, she’s been consulting two days a week in her field, renting out rooms in her house on Airbnb, and slashing expenses.

Popp is looking for full-time work, but being out of steady work for so long is becoming a problem that comes up in job interviews.

“Employers want somebody who is fresh,” she said. “They want someone who has been laid off for two months instead of two years. There is that unconscious bias that there is something wrong with a person who hasn’t been able to find work for two years.”

She’s looked for work in technology, banking, education and the green industry, so far without success. She’s applied for oil jobs, too, though she’s not eager to go back.

“My layoff was, next to my divorce, the worst thing that ever happened to me,” she said. “And you change after that. And there is a fear it is going to happen again.”

I am scared to be part of a team again, because the family that I created in my last job kicked me out

Melanie Popp, a laid-off energy engineer

Joblessness can be “isolating and lonely,” she added. “I am scared to be part of a team again, because the family that I created in my last job kicked me out.”

Jackie Rafter, president of Higher Landing Inc., a Calgary-based company that helps energy professionals transition to new careers, said most of her clients don’t want to return to oil and gas because they no longer trust the industry and believe its future is uncertain.

Many lost their homes, are taking jobs that are way below their qualifications, or are applying for every job in sight only to be rejected, which fuels their trauma, she said.

“This is a whole new paradigm shift that we never had to contend with before,” Rafter said. “It’s affecting people emotionally, financially, professionally, socially and it’s putting a lot of pressures on their families and their careers. And often they get into a panic mode. It’s a real struggle to get them past that.”

There are jobs in technology, manufacturing, real estate, she said, but it will take years to clear the oilpatch’s jobless bulge, and many openings are in the hidden job market, which means they are not advertised because employers don’t want to be inundated with résumés.

Rafter’s company runs the Grizzly Den, a program that helps jobless clients figure out what they want to do next, identify their transferable skills and then appear before a panel of potential employers to talk about what they would bring to their organizations.

The innovative program has been so successful that Higher Landing is part of a pool of employment services providers that receives government funding to help get people off employment insurance.

“You have to figure out what your value is and be able to pitch yourself to those people who are going to appreciate your value,” Rafter said. “Spinning your résumé on social media doesn’t work. You have to be smart and do your homework. But if you can’t explain why you are so different and what makes you so wonderful, how can anyone else?”

People came to work in the morning and there was a security guard who wanted you to leave the office. People worked there for many years. There was no dignity

Dennis Agbegha on what he witnessed as layoffs his the energy patch

Dennis Agbegha is one of Higher Landing’s success stories.

The 38-year-old with a master’s degree in petroleum geoscience from the U.K.’s Imperial College London (which he attended on scholarships) was working for Exxon Mobil Corp. on deep-water prospects off West Africa when oil prices collapsed. He was laid off last year and tried his luck in Calgary, only to find thousands of other geologists on the street.

After working with Higher Learning, Agbegha applied for hundreds of positions at companies ranging from oil companies to warehouses. The lone response came from ATB Financial, the Alberta government-owned bank. He won a job in its call centre and returned to the workforce in February.

He went through the training and loved the environment, but his salary — $40,000 a year — was the lowest he’d had in 12 years. He got a $10,000 raise when he was quickly promoted to a new position in business banking, but he still earns 25 per cent of what he earned at Exxon.

“If you think about it from that perspective, it will make you feel bad,” Agbegha said. “But if I think about the fact that this is my life, this is where I want to be, that I better face the challenge, some day I believe my experience will show up and it’s going to get better. I am always positive.”

He is not even thinking about returning to oil and gas because of the way the sector handled the price crash.

He is not even thinking about returning to oil and gas because of the way the sector handled the price crash.

“There was no human side to it,” he said. “It was just about business. People came to work in the morning and there was a security guard who wanted you to leave the office. People worked there for many years. There was no dignity.”

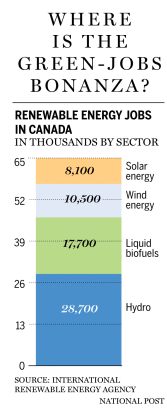

Like other oilpatch workers, Agbegha saw little evidence of green jobs during his search.

Victoria Waye, a Calgary-based recruiter at EnergeiaWorks, which primarily fills jobs in the solar and wind industries for clients in Alberta and Ontario, said openings for green jobs today in Alberta are measured in the “dozens” rather than in the hundreds or thousands.

Those jobs are in maintaining and operating existing facilities, installing solar panels on roofs and installing charging outlets for electric cars. She expects hiring will pick up once companies start building new renewable energy projects under the province’s Renewable Electricity Program.

Alberta’s government has said its Climate Leadership Plan will create 7,000 jobs by transitioning to renewable and natural gas-generated electricity by 2030. Even more promises of green jobs have been made by the federal government, which claimed in its April budget that Canada is well positioned to tap into the global, $1-trillion-a-year clean tech market.

According to the International Renewable Energy Agency, there are 65,100 renewable energy jobs today across Canada. Of these, 28,700 are in big hydro, 17,700 are in liquid biofuels, 10,500 are in wind and 8,100 in solar energy.

It is about restarting their careers rather than picking up where they left off in the oil and gas industry

Victoria Waye, a Calgary-based recruiter at EnergeiaWorks

Still, a mismatch in skills, experience and pay expectations means oil and gas workers are unlikely to land those jobs, Waye said.

For example, in wind energy, “they don’t know who the suppliers are, who the vendors are, what the regulations behind wind are, how to develop the land, how to find the land, any kind of those scenarios that are needed to be highly competitive with other companies that have experienced employees,” she said.

Companies also hesitate to hire trades workers from oil and gas because they’re expected to leave when something more lucrative comes along. Trades jobs in the oilpatch pay $50 to $60 an hour, compared to $20 to $25 an hour in green energy, Waye said.

The picture is no rosier for energy professionals, she said.

A wind project manager knows how to handle everything from finding a site through to construction, while an oil and gas project manager knows bits and pieces of a project and is supported by a large team. As for pay, a project manager earns $100,000-$120,000 a year in the wind industry compared to $200,000 in oil and gas.

“It’s about restarting their careers rather than picking up where they left off in the oil and gas industry,” she said.

That’s exactly what Ryan Lemiski is doing. The 34-year-old geologist with a master’s degree in earth and atmospheric sciences from the University of Alberta in Edmonton is returning to school part time in September to earn an MBA focused on energy from Queen’s University in Kingston, Ont. He hopes it will open doors in the green industry.

About 18 months after losing his job at Nexen Inc., owned by China’s CNOOC Ltd., Lemiski landed a short-term contract that is now over.

Prospects for geologists remain terrible, he said. The few job openings draw hundreds of résumés and tend to be filled by those with very specialized backgrounds, such as experience in the Montney or in the Duvernay.

“In Canada, I don’t think the industry is ever going to be the same,” Lemiski said. “I was waiting for the government to make an announcement on what they are going to do to transition people from energy jobs to other sectors. I haven’t seen anything besides rebates on light bulbs.”

Financial Post

Twitter.com/claudiaoutwest

You can read more of the news on source